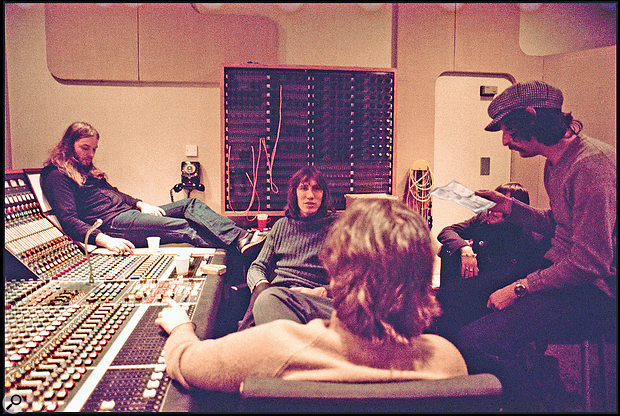

Pink Floyd in the control room of Abbey Road’s Studio 3 with Brian Humhpries (back to camera), during the Wish You Were Here sessions, 1975.

Pink Floyd in the control room of Abbey Road’s Studio 3 with Brian Humhpries (back to camera), during the Wish You Were Here sessions, 1975.

Engineer Brian Humphries tells the story of recording Pink Floyd’s nine-part lamentation to their lost colleague, Syd Barrett.

Celebrating the talent and mourning the absence of former Pink Floyd frontman Syd Barrett, whose mental breakdown precipitated his departure from the progressive rock outfit in early 1968, ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’ is the nine–part opus that, divided in two, bookends the 1975 concept album Wish You Were Here.

It was while writing new material at a studio in London’s King’s Cross the previous year that David Gilmour — who had replaced the talented but troubled Barrett on lead guitar — came up with the four–note sequence that, first appearing just before the song’s four–minute mark, inspired bassist Roger Waters to pen its lyrics. Premiered during a series of French and English concerts along with a couple of other new compositions, ‘Raving & Drooling’ and ‘You Gotta Be Crazy’, it drew negative reviews — most notably that by Nick Kent in the NME — at a time when the band members were finding it hard to remain motivated after the gargantuan success of 1973’s The Dark Side Of The Moon. Consequently, after reconvening for the follow–up inside Abbey Road’s Studio Three in January of ’75, Gilmour, Waters, keyboardist Rick Wright and drummer Nick Mason still struggled to find their muse.

“There were days when we didn’t do anything,” says Brian Humphries who engineered Wish You Were Here. “I don’t think they knew what they wanted to do. We had a dartboard and an air rifle and we’d play these word games, sit around, get drunk, go home and return the next day. That’s all we were doing until suddenly everything started falling into place.”

Previously...

Humphries started as a tape op/assistant engineer at London’s Pye Studios in late 1964. He worked there with anyone from Lena Horne, Nancy Sinatra and Sammy Davis Jr to the Kinks and Pink Floyd, whose More movie soundtrack album was one of his final Pye–based projects before relocating to Island Records’ new Basing Street Studios in 1969. That same year he worked with Spooky Tooth, engineered the live tracks on Pink Floyd’s Ummagumma and also recorded (uncredited) the band’s contributions to the Zabriskie Point film soundtrack. Thereafter, Humphries’ recording and mix assignments included Roger Waters’ compositions on the Music From The Body soundtrack, Traffic, Paul McCartney, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, Black Sabbath, Barclay James Harvest, Stevie Wonder, Jim Capaldi and Mott The Hoople through 1974, when Pink Floyd booked the Basing Street mobile truck to record a couple of concerts at London’s Empire Pool (now Wembley Arena).

“I was asked to go to the second gig at the Empire Pool so that I could check out what equipment would be needed for recording with the mobile,” Humphries recalls. “Then, when I was talking with the band members about old times, I let it be known that I had been doing live gig mixing. So, they asked me to sit down with their sound mixer and give them my opinion of what he was doing. After giving it a listen I told them it was rubbish, especially considering the equipment they had. So, they then asked me to take over doing their live sound for the rest of the British tour, which meant somebody else had to record the remaining Empire Pool gigs.”

Thereafter, Brian Humphries accompanied Pink Floyd on their US visit, taking care of the live-sound mixing. Next, when Dark Side Of The Moon engineer Alan Parsons began focussing on his own Alan Parsons Project activities, Humphries filled his place behind the console for Wish You Were Here. At the same time, he also engineered the band’s American concerts on the East Coast in April 1975 and on the West Coast that June, interrupting the January–July album sessions at Abbey Road where, according to Humphries, “Studio Three had just installed a Studer A80 24–track tape machine as well as an EMI–modified Neve that nobody knew how to operate. We were like guinea pigs and I was the main guinea pig.”

Gremlins

Those sessions took place four days a week, from 2:30 in the afternoon until late in the evening, and the first track that the band members worked on was ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’. This commenced with them laying down a backing track consisting of DI’d bass, synths and acoustic guitar, as well as the drums that were miked by Humphries’ assistant Peter James; an EMI staffer who was familiar with the in–house equipment.

Dave Gilmour recording a guitar part in Studio 3.Photo: Jill Furmanovsky

Dave Gilmour recording a guitar part in Studio 3.Photo: Jill Furmanovsky

“We originally did the backing track over the course of several days, but we came to the conclusion that it just wasn’t good enough,” Dave Gilmour told Gary Cooper in October 1975 for the Wish You Were Here songbook. “So we did it again in one day flat and got it a lot better. Unfortunately nobody understood the desk properly and when we played it back we found that someone had switched the echo returns from monitors to tracks one and two. That affected the tom–toms and guitars and keyboards which were playing along at the time. There was no way of saving it, so we just had to do it yet again.”

Although Brian Humphries has been accused of unintentionally ruining the backing track with echo, he begs to differ. “A certain guitarist with sticky fingers who liked to try things out was responsible for that,” he says. “But, as it was four against one, I got the blame. ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’ was recorded in three different sections, and when I tried editing the first and second sections together the timing was off, so they had to re–record the first one. We could put echo on the control room monitors on certain tracks, and I recall sitting with Rick Wright and him saying, ‘I love the organ. Can you take the echo off?’ I said, ‘I haven’t put any on,’ to which he responded, ‘Well, there’s echo on there.’ And there was. However, I couldn’t get rid of it, and that’s because it wasn’t studio echo, it was down on tape. Nobody — not even the technical people at Abbey Road — knew how the desk worked. Being that I was the first outside engineer to be working there, I felt they were looking for any excuse to get me out of there and have one of their in–house guys do the job. This all happened on a Friday evening and I was expecting to get fired on the Monday morning. Instead the band members just agreed to record both sections again because they felt they could do them better.”

It wasn’t long before Brian Humphries also felt the effects of the rising tension between the band members, with Roger Waters throwing his weight around and Rick Wright bearing the brunt of it. Sometimes caught in the crossfire, the engineer was closest to Wright but wisely chose to protect his job by staying out of the ego–laced intra–group politics. This included Waters deciding that absence resulting from disillusionment with the music business should be the theme of the new album.

As neither ‘Raving & Drooling’ or ‘You Gotta Be Crazy’ suited this subject matter, he suggested ditching them in favour of material that did. And he also proposed splitting ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’ so that, instead of taking up an entire side of the vinyl LP — like ‘Atom Heart Mother’ on the 1970 album of the same name and ‘Echoes’ on 1971’s Meddle — it would commence and end the new record. When Gilmour disagreed he was outvoted by Waters, keyboardist Rick Wright and drummer Nick Mason, and this led to ‘Welcome To The Machine’ and ‘Have A Cigar’ being sandwiched between ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond (Parts I–V)’ and ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond (Parts VI–IX)’ while the discarded tracks would appear as ‘Sheep’ and ‘Dogs’ on 1977’s Animals.

Parts I To IX

On the finished record, Part I commences with the looped sound of wet fingers rubbing wine glass rims, originally recorded for an album titled Household Objects. Rick Wright then builds on this with a Hammond organ as well as the synth sounds of an EMS VCS3, ARP Solina and Minimoog before Dave Gilmour plays an extended G-minor blues solo on his Fender Strat. (As Gilmour was looking for a big, spacey sound, we was tracked in the much larger, orchestra–oriented Studio 1 where his amps were miked from a distance.) Nick Mason’s drumming and Roger Waters’ bass playing then introduce Part II prior to a second Gilmour solo, while his third follows Wright’s Minimoog solo in Part III, which includes a Steinway grand piano overdub. Now backing singers Venetta Fields and Carlena Williams — who, as the Blackberries, have toured with Pink Floyd — enter the picture, harmonising in Part IV before Part V features twin guitars playing the main theme and Dick Parry performing baritone and tenor sax solos that are supported by ARP strings.

The view from behind the Neve console in Studio 3’s control room. Photo: Jill Furmanovsky

The view from behind the Neve console in Studio 3’s control room. Photo: Jill Furmanovsky

An industrial hum heralds the transition to ‘Welcome To The Machine’, the track that ends side one; following ‘Have A Cigar’, an ominous–sounding wind serves as the link between ‘Wish You Were Here’ and ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’ Part VI. A Gilmour bass part is supplemented by a Waters riff; Wright’s synths and an ascending Gilmour lap steel solo precede the vocals that continue into Part VII, while a Gilmour riff comprises the link to Part VIII, featuring Wright’s Minimoog and Hohner clavinet. Finally, Part IX revolves around Mason’s drums and Wright’s mélange of Hammond organ, Steinway grand and assorted synths, culminating in an affectionate nod to Syd Barrett at the fadeout via a brief rendition of the melody to one of his most famous Floyd compositions, ‘See Emily Play’.

“Some of those elements were written during the recording,” Brian Humphries explains. “Roger might say, ‘Look, we need another track. How about this?’ before going into the studio and coming up with some new chord sequences. It was a case of play it by ear quite a lot of the time, but that may not have happened had the sessions not been interrupted by the East and West Coast concert tours. Those interruptions provided the guys with more impetus to write whatever came next. As they themselves have recalled, David would play some chords and Roger would say, ‘Oh, that sounds good, I’ll add some lyrics.’ I didn’t have much input in that process — they decided what they wanted to do and I recorded it — but I did have more say with Richard Wright. Rick had a house not far from the studio, in Notting Hill Gate, and I used to stay there as well. So, when he did his overdubs, the others would often go home and he’d take in a lot of what I had to say.

“There were times when I thought no, this isn’t going the right way. But then somebody would come up with something and everything would click into place. When Roger had an idea it was a case of if you don’t like it, tough, and whereas Rick got worn down by this — increasingly only contributing parts to ensure he remained with the band and was credited on the record — David would grit his teeth and go along with it just for the sake of doing so. Sometimes the ideas worked, sometimes they didn’t, and that’s perfectly normal, but working in that atmosphere wasn’t easy.”

An Unexpected Guest

Neither, for that matter, was the surprise visit that took place inside Abbey Road Studio Three on Thursday 5th June 1975, during the final mix of ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’. Unannounced, an overweight man with a shaved head and virtually no eyebrows suddenly appeared in the control room. No one had a clue who he was — Rick Wright thought he might be a friend of Roger Waters, Dave Gilmour assumed he was a member of EMI’s in–house staff. Then the penny dropped. Recognising the stranger as, unbelievably, the subject of the track they were mixing, Gilmour turned to Nick Mason and muttered, “It’s Syd.”

Brian Humphries today. Photo: Paul HampsonEveryone in the room was shell-shocked. Gilmour and Waters started to cry at the sight of their long–lost friend and former collaborator, transformed into a blank–faced, bloated wreck from what Gilmour later described as the “slim, elegant, if bedraggled and dazed person” he had last encountered.

Brian Humphries today. Photo: Paul HampsonEveryone in the room was shell-shocked. Gilmour and Waters started to cry at the sight of their long–lost friend and former collaborator, transformed into a blank–faced, bloated wreck from what Gilmour later described as the “slim, elegant, if bedraggled and dazed person” he had last encountered.

“He apparently walked into the studio before coming into the control room, but I never saw that,” says Brian Humphries who would subsequently engineer Pink Floyd’s 1977 album, Animals. “Maybe I was talking and didn’t notice. Either way, the doors opened, in came this fat, bald figure wearing a white trench coat, and he just stood there while we all looked around at each other. Then David said, ‘Alright, Syd?’ and we couldn’t believe it.”

When asked the reason for his massive weight gain, Barrett explained that he’d been gorging himself on pork chops. What’s more, having brought his guitar, he announced that he was ready to play on the new record. The irony of his showing up at the precise moment ‘Shine On’ neared completion was lost on no one, except the man himself, who didn’t appear to make the connection. All he had to say about the song was “sounds a bit old”. Otherwise, he spent his time in the studio brushing his teeth and indulging in somewhat nonsensical small–talk. Attending the reception for Dave Gilmour’s marriage to model/artist Virginia ‘Ginger’ Hasenbein that took place in the studio canteen immediately following the session, Syd Barrett left without saying goodbye.

What’s It All About?

Released in the UK on 12th September 1975 and on the following day in the US, Wish You Were Here topped the charts on both sides of the Atlantic en route to being certified six times platinum. ‘Shine On You Crazy Diamond’, meanwhile, has become one of Pink Floyd’s most acclaimed, iconic and widely discussed tracks.

“I think the song is brilliant in its sort of evocation of what Roger obviously felt about Syd and certainly it matches mine,” Dave Gilmour stated in the 2012 documentary Pink Floyd: The Story of Wish You Were Here.

Roger Waters, on the other hand, has issued typically contradictory remarks.

“‘Shine On’ is not really about Syd,” he informed Mike Watkinson and Pete Anderson for their 2001 book Crazy Diamond: Syd Barrett & The Dawn Of Pink Floyd. “He’s just a symbol for all the extremes of absence some people have to indulge in because it’s the only way they can cope with how fucking sad it is, modern life, to withdraw completely.”

Just over a decade later, in the aforementioned Wish You Were Here documentary, he then did an about–turn:

“It’s my homage to Syd and my heartfelt expression of ... my admiration for the talent and my sadness for the loss of the friend. There are no generalities really in that song. It’s not about all the crazy diamonds. It’s about Syd.”