The Buggles: Geoff Downes (left) and Trevor Horn. Photo: Redferns

The Buggles: Geoff Downes (left) and Trevor Horn. Photo: Redferns

The Buggles' JG Ballard-inspired 'Video Killed The Radio Star' hit the number one spot in no fewer than 16 different countries, and confirmed Trevor Horn in his career as a producer in the process.

When, at one minute past midnight on August 1st, 1981, MTV first hit US airwaves, reaching just a few thousand people in northern New Jersey, the words "Ladies and gentleman, rock and roll,” were announced over footage of the space shuttle Columbia's recent launch countdown. Thereafter, the groundbreaking cable network's original theme song was followed by its inaugural video which, in light of the cultural revolution that it hoped to instigate, boasted an appropriate title: 'Video Killed The Radio Star'. Just under two decades later, on February 27th, 2000, it would also be the one-millionth video aired on MTV.

Released in September 1979 and a chart-topper in no less than 16 countries (including the UK, where it hit number one that October), 'Video Killed The Radio Star' was written by Trevor Horn, Geoff Downes and Bruce Woolley, and initially recorded by composer/performer/producer Woolley's band the Camera Club for their album English Garden. However, it was the version subsequently issued by Horn and Downes as the Buggles that became an instant classic; a nostalgic yet techno-savvy rumination on the 1960s' passing of a musical era that had previously been dominated by the radio, focusing on an artist whose career hit the skids thanks to the rising popularity of television.

As per the lyrics, sung and mainly written by Horn, set to music largely composed by Woolley, "In my mind and in my car, we can't rewind, we've gone too far.” In truth, rather than celebrate the new age that MTV was ushering in, the song was merely accepting it as inevitable.

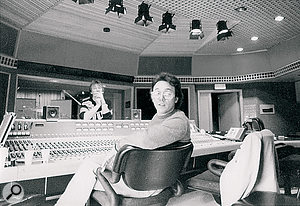

Trevor Horn and Geoff Downes at Sarm East, 1979. They are standing beside the Trident TSM console used to record 'Video Killed The Radio Star'. Photo: Michael Ochs Archive/GettyHorn and Downes first teamed up in 1976 as members of singer Tina Charles's disco-pop backing band; Downes on keyboards, Horn on bass. Charles's Indian-British producer, Biddu, hired both men as session musicians, and his work in the fields of Hi-NRG and electronic disco had a profound influence on Horn's own production aspirations. It was while playing in the house band at London's Hammersmith Palais that Horn met Woolley, and after they and Downes began writing songs that they themselves could record they came up with 'Video Killed The Radio Star' and tracked a demo with Tina Charles performing the lead vocal.

Trevor Horn and Geoff Downes at Sarm East, 1979. They are standing beside the Trident TSM console used to record 'Video Killed The Radio Star'. Photo: Michael Ochs Archive/GettyHorn and Downes first teamed up in 1976 as members of singer Tina Charles's disco-pop backing band; Downes on keyboards, Horn on bass. Charles's Indian-British producer, Biddu, hired both men as session musicians, and his work in the fields of Hi-NRG and electronic disco had a profound influence on Horn's own production aspirations. It was while playing in the house band at London's Hammersmith Palais that Horn met Woolley, and after they and Downes began writing songs that they themselves could record they came up with 'Video Killed The Radio Star' and tracked a demo with Tina Charles performing the lead vocal.

In an interview with The Guardian in 2004, Trevor Horn stated that he had been fascinated by technology's dehumanising effect on society. Accordingly, the inspiration for the song was, he said, "a [JG] Ballard story called 'Sound Sweep' in which a boy goes around old buildings with a vacuum cleaner that sucks up sound. I had a feeling that we were reflecting an age in the same way that he was.”

It was with this feeling in mind that Horn and Downes began hawking the 'Video' demo to assorted labels and attracted the interest of Chris Blackwell at Island Records. Horn, meanwhile, was also garnering personal attention from Sarm Studio's co-owner Jill Sinclair, and this coincided with her signing the Buggles to Sarm's new production company. When Blackwell heard about this, he upped his offer to a level at which Sarm couldn't compete, and the result was that Sinclair released the synth-pop duo from their contract.

"Being that Jill was going to marry Trevor, she was also looking out for his best interests,” says Gary Langan, who, as one of two engineers to record 'Video Killed The Radio Star', also took care of the mix. "It worked out well for everyone.”

White City To Brick Lane

Gary Langan as he was when photographed for an SOS feature on Jeff Wayne's War Of The Worlds in 2005.

Gary Langan as he was when photographed for an SOS feature on Jeff Wayne's War Of The Worlds in 2005.

This included Mr Langan. Born in 1956, he is a native Londoner who, as a kid, was faced with a simple choice during his school holidays: either help his mother at her hairdressing salon or hang out at BBC Radio's White City and Portland Place facilities while his father played violin, saxophone and clarinet on sessions for the Beeb's Light Programme.

"That wasn't a difficult decision,” he says. "Having sat on a piano stool from the age of seven and discovered I didn't really like performing, I found myself in recording studios at the age of 12 and, by the time I was 14, my heart was set on making music that way, behind the console. Hanging out with Dad at those BBC studios, as well as at IBC, I'd watch these guys in white coats work in booths that were equipped with what in those days looked like huge amounts of electronics. Actually, they were using a four-channel mixer for BBC sessions that were cut straight to disc and broadcast the next day.”

In 1974, while Gary Langan was studying for an electronics degree in telecommunications, he interviewed for a job at Trident Studios in Central London and, after impressing owners Norman and Barry Sheffield, he then missed out on the opportunity because, as he puts it, "I hadn't yet learned how to lie. Like a naïve little idiot, when it came to filling out the application form I entered my real age and they had to tear it up. In those days, the GLC [Greater London Council] licencing laws stated that you couldn't work after certain hours if you were under the age of 18. I was 17 and three quarters...”

Soon after, Langan's father ran into some people from Sarm Studios during a gig at The Dorchester Hotel, and discovered that there was an opening for a tape-op-cum-tea-boy at their newly constructed studio on East London's Brick Lane. Two days later, Gary interviewed for the job and, having now learned to stretch the truth, he passed the test, quit college and entered the music business. As an assistant, he subsequently worked with acts such as David Cassidy, the Drifters, the Bay City Rollers and Queen — including the albums A Night At The Opera, A Day At The Races and News Of The World — before eventually becoming Sarm's Chief Engineer and bumping into Trevor Horn.

When Gary Met Trevor

Hugh Padgham, who co-engineered 'Video Killed The Radio Star' — although not according to the NME...

Hugh Padgham, who co-engineered 'Video Killed The Radio Star' — although not according to the NME...

"Sarm was one of two 48-track studios and Trevor needed to put a tambourine on a demo that he was doing,” Langan recalls. "He'd run out of tracks, so he turned up on our doorstep and went 48-track to add the tambourine.

"At that time, punk music was happening and I was not into it. In fact, there was only one punk record ever made at Sarm and that was the Boomtown Rats' first album. So, without realising it, I was looking for something different and then along came this guy called Trevor Horn who had a whole different approach to making a record. He'd do mad things like just recording a bass drum while having the drummer dummy-play the other parts on his knees or on loads of tea towels covering the snare and toms. Then we'd record the hi-hat followed by the snare. It was a completely different way of working.

"Trevor was also one of the first guys to start fooling around with drum machines. The Roland TR808 — boy, Trevor could make that sing. That was one of the great early tools. We hit it off immediately and that has continued throughout our career. We recently worked together on a new Seal album — with, in typically complicated Trevor fashion, him in LA and me doing real-time strings and brass in London via ISDN and Skype — and there's still a great chemistry between the two of us. Like a bass player and drummer in the same band, we don't actually have to talk about things; we can just get on and do them in the knowledge that whatever each of us are good at will be taken care of. That's because we have worked together, off and on, for so long. However, in the early days Trevor was ruling things with an iron rod and he wouldn't accept compromise. That just did not come into it.

"In those days, decisions were made there and then. So, if, for example, one of Geoff's keyboards needed some chorusing and reverb on it, you would record it that way. Whereas today everyone sits around and goes, 'Well, we could do this or we could do that,' you made decisions and those decisions then influenced the next process.”

As it happens, Langan wasn't initially involved in the recording of the Buggles' debut single. That honour fell to Hugh Padgham, then a resident engineer at Richard Branson's Townhouse Studios in West London, where he tracked most of the instruments on 'Video Killed The Radio Star'.

"Hugh and I were always jostling with one another,” Langan says. "As tiny as Sarm was, we were turning out big records, including those three Queen albums, Foreigner, Ian Hunter and the Strawbs. At the same time, Hugh was getting involved with big projects over at The Townhouse, and after he worked there on 'Video', recording Paul Robinson's drums, Trevor's bass and Geoff's keyboards, I stole that song off him by persuading Trevor that he should come to Sarm to finish it off. That's how I ended up doing the vocals, some overdubs — including Bruce Woolley's guitar — and the mix.”

Sarm East

The Buggles in the early 1980s.

The Buggles in the early 1980s.

In 1979, Sarm had recently replaced its Trident B-range console with a 40-input Trident TSM. This was housed inside the same control room as two Studer A80 24-track machines and outboard gear that included an EMT 140 echo plate, Eventide digital delay, Eventide phaser, Marshall Time Modulator, Kepex noise gates, Urei and Orban EQs, and Urei 1176, Dbx 160, and UA LA2 and LA3 compressors.

"That whole studio was so tiny,” Langan recalls, "it's astonishing the calibre of work that came out of this basement at the bottom of Brick Lane. I was taught really well by a guy called Gary Lyons who recorded the first Foreigner album, as well as by Mike Stone, who engineered the Queen albums. I had these two great mentors and we turned out some fantastic stuff. The ceiling height in the studio might have been two metres — if that — and yet it was fun because we made everything work by pushing the equipment that we had to the limit. What's more, because we were in the basement of this little office block, after everyone else in the building had gone home we could feed stuff through speakers into the concrete stairwell.”

For 'Video Killed The Radio Star', Trevor Horn was determined to obtain an in-your-face sound that grabbed the listener's attention.

"If you listen to that record, the level of the bass drum is just ridiculous,” Langan remarks. "At the same time, the backing vocals are bone dry and panned left and right. The great thing about working with Trevor is that he knows when something is not right. He will keep leading you on and making you jump through hoops, and then, when it is right, he knows when to stop. I've always said that working with him is like running a marathon.

"For his lead vocal on 'Video', he was looking for something different. In those days, he wasn't the world's best singer — like a fine wine, he has improved over the years. So, to help disguise the vocal he wanted a sort of telephone voice, and I therefore sat there for a few hours and put it through some graphics and lots of compression. There were absolutely no dynamics left in it whatsoever by the time it had been recorded, pumped back out through a Vox AC30, and then compressed and EQ'ed again. Beforehand, we'd tried using a bullhorn but it really was harsh — the task was to make the vocal loud without cutting your head off. It still had to retain some softness to it, and it was the AC30 that really gave it that quality.

"To record his voice, I would have used a dynamic mic. I'm a great lover of dynamics. Yes, you can have your fabulous [Neumann] U47s and 67s, and they're great for vocals, but when you want something with a bit of guts, a bit of character, go find yourself some good dynamics and you'll be absolutely OK. For 'Video', I would have therefore miked him with [a Shure] SM57 or SM58, or a Sennheiser 421, or we might have even tried an STC 4038 ribbon. And, to get what he wanted, I comp'ed his performance, which in those days was hard work. It was almost like playing a keyboard. As an engineer, you had to play the mute buttons and faders. Bearing in mind that not many tracks were available, we'd do four or five vocal takes and I'd have to be adept at cutting in halfway through words and syllables. Comp'ing a vocal old-style was a real skill.”

So, for that matter, was mixing to Trevor Horn's specifications.

"My work on 'Video Killed The Radio Star' seemed to go on forever,” Langan says. "I must have mixed that track four or five times. Remember, there was no total recall, so we just used to start again. We'd do a mix and three or four days later Trevor would go, 'It's not happening. We need to do this and we need to do that.' The sound of the bass drum was one of his main concerns, along with his vocal and the backing vocals. It was all about how dry and how loud they should be in the mix without the whole thing sounding ridiculous. As it turned out, that record still had the loudest bass drum ever for its time.

"Sometimes it isn't good to creep up to the mark. You might as well just go from one end to the other in production terms and then pull back. You know, make some really bold statements. So when Trevor was hacked off that the bass drum wasn't loud enough, I'd think, 'OK, now we're going to do a mix with it absolutely loud!' My nickname was Cocky, and after I'd do the new mix he'd go, 'Alright, Cocky, I get the point.' I'm a great believer in not mucking about in the middle. Nobody remembers what goes on in the middle, but everybody remembers what was first and what was last, so I think it's really, really important to go with that.

"I was trying to impress Trevor because I knew I was good. I liked him and I liked what he was doing, so I really did bust my balls to make the guy happy by trying to achieve what he had in his head. It was a challenge and I've always been up for a challenge. Everything I've ever done has been about the challenge. However, I also have to say that, by the fourth time around on this mix, I was thinking, 'Oh, for God's sake. What am I going to do now? What does this guy want?' That's how I came up with putting his voice through the amp — he was forcing me to push myself beyond where I'd gone before. By and by, we ended up having a really good chemistry, and that also included Geoff. I'm not sidelining Geoff. He was a masterful keyboard player, but Trevor really was the driving force. I could probably count on two fingers any point at which he and I have fallen out over the past 30-plus years. It has always been a great relationship.”

The Age of Plastic

After 'Video Killed The Radio Star' had secured the Buggles a contract with Island Records, Horn and Downes had to write material for an album. This, in turn, led to further sessions at Sarm with Gary Langan sitting behind the TSM console, and soon the three men developed a system of working together.

"We recorded to a click track using the TR808,” Langan recalls, "and we had various machines and boxes that supposedly sync'ed everything up. I'd feed the time code from the A80s into this box that would spew out some funny code for the TR808 to use. Everything was done to a click. Trevor is a complete feel merchant, and for him it's all about precision. So we went through the process of recording the rest of the album, and in those days of relatively limited technology we again had to push what we had to the limit. We had to be creative. If, for instance, something required an effect, whether it be tape delay or phasing or some big, delayed reverb, the art was to get that effect right and record it. We didn't have enough channels and other resources to be able to sit at the mix and say, 'OK, I want to phase this, I want to do that, I want to do that...' It all had to be done and then, as I said, it would influence the next process.

"When it came to things like a backing vocal balance, we didn't have a terabyte of storage. So we'd make it as clean as we possibly could, bounce that down to two tracks and then we'd erase. We had to be confident and bold, because we really didn't have the room to move, and in that respect, 'I Love You (Miss Robot)' was one of the best mixes I've ever done. I remember, it was a Sunday, it was very, very late and, as per usual, we were running behind. I started at around 11pm or midnight, finished it at three or four in the morning and still to this day it's a pukka mix.

"As a great believer that a mix should have a feel to it, I think that in some warped way I'm a weird musician. What differentiates a good mix from a bad mix is the feel factor — it's got to feel great. When I listen to some mixes I think, 'It's out of whack. That's not a great feel.' Mixing is a real art form. So is recording. But they are different. They require completely different skills. I think I could teach anybody to record something; I don't think I could teach anybody to mix something, and that's because it's got to come from within you. It's all about the feel. When you're recording, the feel is coming from the musicians and, as the engineer, you're just getting things from A to B in the most expedient way possible. However, when it comes to the mix, all of the musicians are gone, the stage is cleared and now it's your stage.

"You have two feelings inside your body; you've got the head feeling and what I call the tummy feeling. The head feeling is a liar — it trips you up, it tricks you, it tells you false truths. The feeling in the bottom of your tummy — that's when you know it's fantastic. I'd say all of the mixes on that first Buggles album are really good, but for me the best one is 'I Love You (Miss Robot)'. On the other hand, 'Video' was the most difficult because it was the first single. I don't think we remixed any of the other tracks as much as that one.”

Postmortem

The version of 'Video Killed The Radio Star' that appears on the Age Of Plastic album is, at 4:13, about 48 seconds longer than that issued as a single, and this is due to the regular fade-out segueing into a piano and synth coda that ends with a brief sampling of the background vocals contributed by Debi Doss and Linda Jardim. Indeed, it is their bright and vociferous repetition of the chorus that, added to the layers of then-state-of-the-art synthesizers, provides the song with its timeless quality and, paradoxically, also serves as a snapshot of the late '70s and early '80s.

Released in the UK on 4th February, 1980, The Age Of Plastic ran with this theme, musically promoting modern technology while lyrically raising concerns about its impact. Accordingly, the record's opening track, 'Living In The Plastic Age', was also released as a single, along with 'Clean Clean' and 'Elstree', yet none came close to rivalling the global success of 'Video Killed The Radio Star' which earned Gary Langan — not Hugh Padgham — an 'Engineer Of The Year' award from The NME.

"It was far more fun to be creative back then, Trevor understood that and The Age of Plastic was a great album,” asserts Langan, who would subsequently co-found ZTT Records with Trevor Horn, Jill Sinclair and music journalist Paul Morley, in addition to forming avant-garde synth-pop outfit The Art Of Noise with Horn, Morley, programmer JJ Jeczalik and arranger Anne Dudley.

"I've got to tell you,” Langan continues. "I've had such a great time making records. Today, it isn't the same, and that's why I do live work.”

Indeed, with studio production and engineering credits that range from ABC, Big Country and Spandau Ballet to Public Image Ltd, Sarah Brightman and Natalie Imbruglia, Gary Langan is now also immersing himself in the concert sound for various live acts. His first foray into this field was for Jeff Wayne, recreating The War Of The Worlds live.

"I love getting to fiddle with faders,” he says. "When I'm doing a front-of-house mix, I'm there, I'm animated. Lots of front-of-house guys just stand there with their arms folded once the gig gets going. Not me. I'm changing the compression levels on the vocals, as well as the delays and the EQ for every song. 'Hey, for some reason the vocal's suddenly sounding a bit edgy — let's dive in and do something about it.' I can do all that, I can multi-task. What I can't do is just sit and push a mouse around. I come from a world where you sit and make the equipment sing. That's what Trevor and I used to do — we'd really make the equipment sing. And you can hear that with the Buggles. Their music pushed a lot of boundaries and made a lot of people think.

"When people are listening to what you've recorded, you want them to question it. It's like a great book, a great movie, a great play or a great poem: it's got to invoke questions and draw you in. Working with Trevor taught me so many things: don't accept compromise, don't sit back on your laurels, have passion for what you're doing and go that extra mile, because it will pay off. It's the payback factor and that is what Trevor has always been brilliant at. I love working with him.”

I Love The Smell Of Ampex In The Morning!

"Yesterday, while going through a pile of old vinyl records at home,” says Gary Langan, "I found acetates of the Buggles. Here I was, about to do this interview, and I thought, 'I don't believe it.' Those acetates still smell amazing; a hard drive's got no smell. With classic tracks of the '70s and '80s, you'd go to the mastering room and smell those acetates. Then there was the smell of tape — oooh, opening a box of fresh tape first thing in the morning! That may sound daft, but it was great. There was something sexy about it. A fresh reel of Ampex — whooar! You don't get a bloody hard drive out of a box and go, 'Whooar, that's fantastic.'

"Back then, it was about lining up the tape machine; now it's about file management. And then there was tape editing. That was another great tool. Trevor's multitracks would look like a zebra-crossing. You know, 'I want that middle eight from take three.' We'd physically remove the middle eight and insert it into another take, and there was an art to doing that. Then, if the edit didn't quite work, there was the art of rubbing the edit across the heads so that bits of iron filings smudged it. Again, he might say, 'No, I can still hear the edit,' so I'd give it another go. Standing over me, Trevor would ask, 'What are you doing, Cocky?' and I'd say, 'I'm making the edit sound great, Trevor,' while taking out one millimetre of tape.

"Going back to the days of tape, no track that I did with Trevor wasn't edited. He's ruthless. In line with his request, I'd remove the chorus or middle eight from take five and insert it into the master, and then he'd sit and listen and go, 'Nah.' So I'd then have to pull that part back out, put the original one back in and he'd say, 'No, we've got to go and look further... Why don't we have half of take five, half of take four, make that the middle eight and put that in?' I'm telling you, editing was a real tool. As it is now. It's just that it was an art form in those days.

"When I was lecturing in Japan for SSL, I was taught to edit with a pair of scissors. Up until then I had been using editing blocks, but this Japanese guy showed me how to edit with a pair of scissors. I tried to employ that when I returned to the UK and everybody thought I was nuts. 'OK, tell me I'm nuts, but does it work?' 'Yeah, it works, but you're still nuts.'”