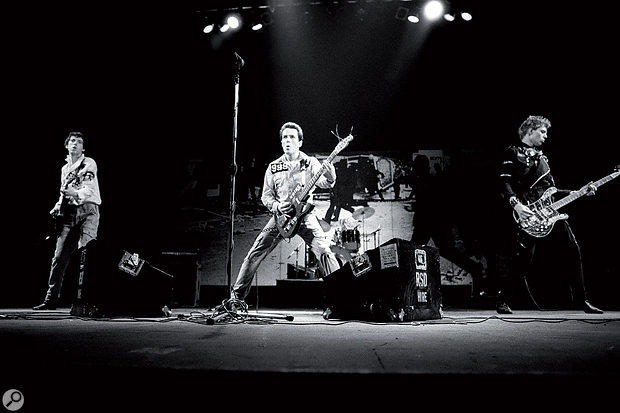

The Clash on stage at the Rainbow Theatre, 1977. From left to right: Mick Jones, Joe Strummer and Paul Simonon.Photo: Redferns

The Clash on stage at the Rainbow Theatre, 1977. From left to right: Mick Jones, Joe Strummer and Paul Simonon.Photo: Redferns

When the Clash entered the studio for the first time they were determined not to sacrifice their punk principles, and the fates — not to mention a sympathetic engineer and a negligent record company — were on their side...

On 30th August 1976 the Clash's frontman Joe Strummer, bassist Paul Simonon and manager Bernie Rhodes were attending West London's Notting Hill Carnival when all hell broke loose. Amid this annual celebration of Caribbean culture, the police were attacked for apprehending a pickpocket, resulting in the hospitalisation of more than 100 PCs and 60 members of the public, as well as widespread media reports about how black youths were involved in bloody confrontations with white officers. In fact, the rioters also included numerous whites, but their efforts apparently weren't enough for Strummer. After witnessing the debacle that unfolded before his very eyes, he felt inspired to write a song exhorting young white working-class Brits to be as outraged and proactive as their black counterparts in the face of government oppression.

"The only thing we're saying about the blacks is that they've got their problems and they're prepared to deal with them,” the singer-guitarist explained to the NME in response to accusations that his band's explosive first single, 'White Riot', was encouraging a race war. "But white men, they just ain't prepared to deal with them — everything's too cosy. They've got stereos, drugs, hi-fis, cars. The poor blacks and the poor whites are in the same boat.”

Released in the UK on 26th March 1977 the Clash's debut record created immediate headlines and caused concert promoters to request that the punk outfit refrain from performing it after the song provoked audience brawls at some of their shows. Before one gig, Strummer and lead guitarist-composer Mick Jones actually got into a dressing-room fight of their own when the latter didn't want to play the number. The song was never one of his favourites, yet it would come to be regarded as a classic among the band's legion of followers.

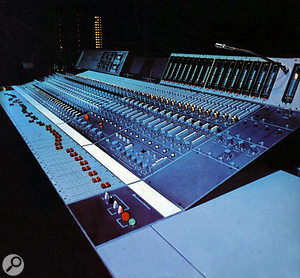

The Neve desk in Whitfield Street's Studio 3.

The Neve desk in Whitfield Street's Studio 3.

This rabid fan base had expanded rapidly since the Clash's live debut, supporting the Sex Pistols at the Black Swan in Sheffield on 4th July 1976 less than a month after Strummer had joined. On 29th August of the same year, the day before the Notting Hill Riot, following extended work in their Camden rehearsal studio and Strummer-Jones writing sessions in the office above, the Clash had then performed their second concert, once again opening for the Sex Pistols — this time in tandem with the Buzzcocks — at Islington's Screen On The Green. It was a seminal event in the annals of the British punk movement, yet it didn't take long for that movement to be undermined by what many diehards perceived as some of its central artists selling out.

A prime example was the Clash signing a £100,000 contract with CBS Records in January 1977, even though the group had still played relatively few gigs, all as a support act for the Pistols, never as the headliner. By then, guitarist Keith Levene had departed the line-up and several men had occupied the drummer's seat: Pablo LaBritain, Terry Chimes and Rob Harper, before Chimes rejoined in time for the group's initial recording sessions that February inside CBS Studio 3 on Whitfield Street in Central London.

An Education

Studio 3 live room, from the Whitfield Street catalogue.

Studio 3 live room, from the Whitfield Street catalogue.

"'White Riot' captures the quintessential sound of the Clash and I think I had a lot to do with that,” says Simon Humphrey, who engineered the track as well as the band's self-titled first album. "They were given free rein by the record company and at no point did I question the validity of what they were doing. So many other engineers would have tried to polish that recording, and it isn't polished. It just is what it is — a working-class riot, not a middle-class one — and that's why it's great.”

A native of South-East London, 18-year-old Humphrey landed a job as a tape-op/tea boy at CBS Whitfield Street in 1973 and soon began assisting on a wide variety of sessions. Within two years, he was engineering, and among the eclectic array of artists whom he recorded were guitarist John Williams, jazz singer George Melly, actors Michael Crawford, Peter Ustinov and Vincent Price, poet laureate Ted Hughes, comedian Tommy Cooper, the English Chamber Orchestra and chart acts such as Abba, Argent, Marc Bolan, Bill Haley, Duane Eddy, the Glitter Band, Hot Chocolate, Tina Charles, Sailor, Smokie and David Essex (even making a brief cameo appearance in Essex's 1975 film Stardust).

"In the morning you could be doing a classic session, followed by a pop session in the afternoon and then a jingle the next day,” Humphrey recalls. "The music at CBS Whitfield Street came in all shapes and sizes, and so my education as an engineer taught me to be very open-minded about who I worked with. It didn't matter if I liked or understood the material I was recording, I just had to be professional and do the best possible job for whichever client walked through the door. I'd be sitting there with no idea as to what kind of session had been booked — an avant-garde piano recording, jazz, classical, pop, spoken-word, you name it — and have to turn my hand to anything using the same basic tools. There were no special techniques that I applied to one thing that I didn't apply to another; at least, if there were, no one bothered to teach me them. I just made it up as I went along, applying what I'd picked up from other people and, what with the variety of artists, every day was a joy.”

Before Retro Was Cool

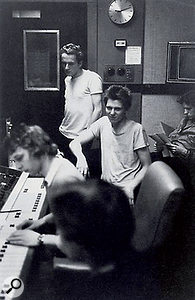

Simon Humphrey and the Clash in the control room of Whitfield Street's Studio 3. Photo: Caroline Coon

Simon Humphrey and the Clash in the control room of Whitfield Street's Studio 3. Photo: Caroline Coon

CBS Whitfield Street had three studios and a mix room, as well as several cutting rooms and dubbing suites.

"Studio 1 was a huge room, used for classical, Studio 2 was the mid-sized room, and then up top was Studio 3, where I was placed as a junior engineer,” says Simon Humphrey. "It had a very basic 25 x 25 foot live area — like a moderately large lounge, with no windows, no vocal booths — and an 18 x 15 foot control room with an old 30-channel Neve console that had been there since the late '60s, when the place was known as Bond Street Studios. Although the MCI desks downstairs were much more up to date, this one had a great heritage in terms of the artists it had recorded, but it also predated phantom power. As a result, Studio 3 only had valve microphones — mainly [Neumann] U67s and KM 64s — and so we were left to deal with a vintage setup that was pretty odd in 1977 when I recorded the Clash.

"Back then, a desk that needed valve microphones was regarded as a bit of a joke. After all, when I started in the early '70s, valves were something that your granddad used. There was no fashion for them whatsoever. What's more, if you have 20 valve microphones running at the same time, two or three of them will usually pack up on you, so it was a very unreliable setup. That's why Studio 3 was basically seen as the demo studio; not the best-sounding studio, more of an afterthought. Of course, all these years later we love the old Neves and anything to do with valves, but that wasn't the case in the mid-'70s. Shortly after I left in 1979, that desk with all its heritage was just scrapped and thrown away. It was seen as having no value, which is a shame, and all of those old microphones were packed up and put in a cupboard. Only 10 years later did another generation of engineers come along and dig them out of there.”

The other not-so-state-of-the-art equipment housed inside Studio 3 included a Studer A80 16-track tape machine, a Studer A80 quarter-inch machine for mixing and JBL 4350 main monitors, along with Neve in-console compressors, Urei LA4 and 1176 outboard compressors and EMT 140 echo plates, supplemented by no less than four basement echo chambers.

"CBS Whitfield Street actually owned a couple of Fairchild limiters and some parametric EQs, but as a junior engineer I wasn't allowed to use any of that equipment,” Humphrey recalls. "There was a sort of hierarchy and you had to be a senior engineer to use that gear, so the choice of equipment in Studio 3 was very, very limited.

"Without a doubt, the Clash were very deliberately booked into there. The record company wanted them out of the way, four floors up, where those unruly punks couldn't cause any trouble. The studio's management never went up there, but I loved it; almost like an attic that you could make your own, with no passing traffic and lots of privacy. The room itself was square, and it had a parquet floor and absorbent walls, so the sound in there was pretty dead. Looking from the control room I could see the drums in the far-left corner, the bass amp in front of the drums and then the guitar amps at near left. This meant they were positioned in a straight line, separated by screens, while Joe Strummer, Mick Jones and Paul Simonon could occupy the rest of the space that wasn't taken up by the acoustic piano.”

Communication Problems

Simon Humphrey at The ChairWorks in Yorkshire, where he is the resident producer.

Simon Humphrey at The ChairWorks in Yorkshire, where he is the resident producer.

"The second time I met Joe, he came in and plonked his amp right next to Terry's drum kit. I said, 'You can't put your amp there, Joe, because we'll need to get some separation between you and the drums.' That was the standard procedure, but his reply was, 'I don't know what separation is and I don't like it,' said in that very aggressive, punky way. He later said that he did in fact know what separation was and he was just having a joke with me, and that's probably true, but all I can say is that the initial recording setup was me trying to wrestle with them in terms of how things were going to get done. I only knew what I had been taught and these guys were coming in with an attitude.

"Joe knew I had recorded Abba, and the next conversation we had, very soon afterwards, started with him asking me, 'How do you normally record? Where do you mic stuff up and what do you do with the drums?' So, I told him, 'I normally do this and that,' and he said, 'Well, we don't want you to do any of that.' I thought, 'This isn't going to work. I can't avoid doing what I've learned works best. This is just punk bullshit.' Clearly, they were trying to assert themselves and, while I was trying to figure out if there was an element of joking in all of this, they were definitely attempting to make their mark early on. Unsure as to whether this was going to work out, I also had to get on and do my job.

"Joe telling me not to do anything I'd done before really resonated with me. I knew this was punk and this was new, but I also wasn't stupid enough to just go along with whatever they wanted. Still, it did stick with me, and so I subsequently had to figure out a way of recording them that would work for all of us. This meant jockeying for position early on, and the idea of not doing what I'd learned before was really at the heart of how I approached recording the band. I felt there was some relevance to what they were saying; they didn't want to sound like what had gone before and they certainly didn't want to sound like the sort of things that I had done before. Those mid-'70s drum sounds had been very dead, damped and ploddy, everything had been isolated, and I knew they didn't want that. Instead of separation on the instruments they wanted to kick doors down, but I also had to make a recording that worked.

"As a house engineer, I wasn't allowed anywhere near a production credit at that time. So, they brought in a guy named Mickey Foote who was essentially their live sound engineer and gave him the job of producing, acting as a sort of intermediary between me and the band. He was a communicator, someone they trusted, but I don't recall him having anything to do with what I actually did. I think they just used him as a foil. Until the mid-'70s, most musicians were very much expected to be on the other side of the glass and not interfere with what took place on our side. The Clash, however, wanted to look through the glass to the control room and see someone they knew, trusted and could occasionally communicate with. Mickey was that person, even though I don't remember him taking on the role of producer at all. In fact, after the initial sessions, once Mick and Joe had worked out I was someone they could communicate with and that I wasn't a dickhead, Mickey became surplus to requirements.

"I have got nothing against Mickey. He's got his name on the album, he was a good friend to them and he was a good professional, but he didn't necessarily need to be there. The band needed to record, they needed a studio and they needed an engineer, and so that was the important relationship that had to be cultivated. They absolutely were not going to work with an established producer of the day because they weren't going to be told what to do.

"Having been given the job of recording the band, that responsibility was on my shoulders. While they wanted to get on with it, I had no idea if they'd recorded before. All the evidence was that they hadn't and they were giving nothing away whatsoever, including the fact that Joe and Mick had previously been in other bands. And even if they did have prior experience, they didn't want to apply that knowledge to these particular recordings. They wanted them to be fresh and different, which is why I had to take on board all of their suggestions.

"In 1975 and '76, I was a long-haired hippy whose favourite band was Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. Then punk came along and, having recorded Abba and been into very well-crafted Californian harmony rock, it was quite a shocker in 1977 to suddenly hear this raw sound. Mick and Joe would play something in the studio, look at Mickey and me and shout, 'How was that?' They'd want a reaction but I genuinely didn't know if it was good or not. So, trying to be diplomatic, my default answer as an engineer was 'Well, it wasn't bad, but you can probably do better.' Their response would be 'Oh great, we'll keep it then!' They'd always try to second-guess you. If you said it wasn't very good, they'd almost certainly want to keep it, and if you said it was brilliant, they'd probably want to get rid of it. In other words, anything I liked was obviously wrong whereas anything I hated was obviously right.

"After a few days, we reached the stage where I began to second-guess them. If Mick played a terrible guitar solo, I'd say, 'Yeah, that's great, Mick,' and he'd go, 'Are you fucking joking? It's terrible!' That's how our relationship initially developed until, eventually, we learned to trust each other. There were certainly tiring and exasperating elements to the whole experience, one of which was that the band had a lot of hangers-on and external people who'd want to angle in on what we were doing.

"Sometimes one of them would come in and say something along the lines of 'What this needs here is the sound of a machine gun going off.' I'd think, 'Oh Christ, what's going to happen next?' before someone would then bring in an air pistol and I'd have to record them firing it. Of course, it would sound terrible, but we'd still have to go through the process of recording these terrible things: bashing a sheet of corrugated metal, throwing it down the stairs or kicking in a plate glass window. 'Why don't we record that?' 'Oh God, here we go again...' It was that whole punk ethos.

"Another fairly exasperating thing was the fact that Paul, the bass player, wasn't interested in talking to me at all. And I also had to earn Joe's trust over a period of time. I don't think he was reticent towards me; he was just reticent towards anyone or anything connected to all the things he didn't like. He was still smarting from all the bad press he and the other guys had got for signing to CBS; they were suffering the consequences of that whole corporate connection and were therefore sparring with the likes of me because I was employed by a company. And their manager Bernie Rhodes was a fairly disruptive influence. He'd wander in, say something controversial and just wind everyone up. Even Mick would tell him, 'Why don't you piss off? You're just getting in the way.' So, there was a lot of posturing going on and, although it was fun, it was hard work to get to the fun bit.”

(Mostly) Smash The Conventional!

Despite Joe Strummer admonishing Simon Humphrey to break with convention when recording the Clash, the latter took a fairly standard approach in terms of miking the instruments: an AKG D12 on the bass drum, a Neumann KM64 on the snare, Sennheiser 421s on the toms and valve Neumann U67s as overheads. The guitar amps were also close miked with U67s while the bass was DI'd and miked with a Neumann U47. A U67 was used to track Strummer's vocals.

"Back then,” Humphrey explains, "the attitude of a lot of engineers was 'You're the musicians, I'll handle the sound. If you've got a bad sound, I'll fix it. I'll take away your crappy amp and put a nice one in its place.' When it came to the Clash, however, the sound they made was what I was going to record. There was no question of me saying, 'Your guitar doesn't sound acceptable so I'm going to give it a magical sound that will make you think I'm a genius.' I knew very early on that they wanted me to record them, warts and all, and that's what I did.

"Joe had this Fender Telecaster which was like this beaten-up old rusty guitar — obviously his punk special; it was very much him — and he plugged it into this Fender Twin reverb. It made a horrendously toppy, hideous sound, and Mick said, 'God, that's awful.' However, we never, ever thought about trying to improve it, we just thought, 'This is what it sounds like and this is what we're gonna have.' I didn't try to change them. I was only interested in recording them the way they wanted to be: the truth of how they sounded and what they wanted to be, in the raw. As a result, that first album sounded raw beyond belief — shockingly raw — whereas the Sex Pistols' records sounded fantastic. They were very radio friendly and very well produced. Well, the Clash record didn't sound like that at all, but it did sound like them.

"Previously, I had recorded the Glitter Band with [producer] Mike Leander, and to achieve his drum sound he'd quite literally place a blanket over the entire kit. That was the most extreme case of damping I ever saw, but in the mid-'70s most producers and engineers did do the same in a slightly toned-down way, with two towels on the toms and that kind of thing. Everything sounded neat, tidy and damped, but I knew the Clash didn't want any of that, so I had to be very hands-off. When I miked the kit, there was no damping, there was no tuning, and this suggested what New Wave was going to be: the whole New York/Blondie sound. Drum sounds would explode in the late '70s.

"The heavy damping of drums had stemmed from the Pink Floyd Dark Side Of The Moon sound, and that's what I'd spent the past few years trying to get right. Now, I was going for the exact opposite, and it was very exciting. Being that the room we were in wasn't particularly geared towards that, we ended up with a sort of thin quality, and while it wasn't fantastically sophisticated, it totally suited the mood of how the band wanted to sound. It's just so uncompromising when you hear it and just so unsubtle. Famously, the American record company wouldn't release the album because they didn't think it was technically good enough for radio. Yet, when the first single, 'White Riot', came out, it charted immediately in the UK, and on the radio it stood out because of what we hadn't done to make it sound 'nice' like everything else. It wasn't a case of what I did, it was a case of what I didn't do.

Rough Edges

"Joe was a brilliant frontman, a brilliant vocalist and I loved recording him. He just went for it. I don't think he spent more than 15 minutes doing any of the lead vocals. Two or three takes and that was it. When the Clash performed live on stage, Joe was a very physical performer, singing and playing at the same time, and when we'd ask him to do his vocals in the studio he couldn't do so without playing the guitar. He had to do both together. Being that he didn't sing when we recorded the backing tracks, he overdubbed the vocals on his own, and he had to face away from us as he didn't want to see the control room while performing the songs and playing the guitar at the same time even though it wasn't plugged in. If you listened to his isolated vocal tracks, you could hear his Telecaster being hit all the way through because he couldn't detach one from the other.

"You couldn't take the guitar off him and I thought that was great. Other people might have said, 'Listen, Joe, you've got to put the guitar down, learn how to use the mic and learn that connection between you and the microphone.' That's the stuff most singers learn, but Joe wasn't interested in any of that. He just wanted to get the lyrics out and onto the record. It was a physical process for him and he wanted it done as quickly as possible. All day long he'd be drinking honey and lemon while moaning about his throat, and he'd always give it 110 percent. He was a great performer. When you listen to those vocals, what he was bawling out really comes across. I love it.

"Joe wasn't interested in double-tracking or editing vocals. When you recorded a lead vocal with him, it was basically a performance from start to finish. Afterwards, he'd ask whether it was good or not and, based on the answer, he'd either do it again or he wouldn't do it again. You see, if I said, 'Maybe you could do that second verse better, Joe,' or 'Do you really think that was in tune at the end?' he'd immediately go, 'Great, we'll keep it.' I learned very quickly that he and the other guys didn't want the rough edges knocked out in any way, shape or form, so they all got left in and that's one of the reasons why what you hear is so great.

"The reason I was able to do that is because the record company execs never A&R'd the album at all. They simply left the band in the studio with me. We recorded it and mixed it, they put it out, and not once did they question what we did. I wasn't asked to remix anything and not once was I sent back into the studio to repair anything.”

All of which is a bit puzzling since Mickey Foote was a novice producer with absolutely no track record and Simon Humphrey wasn't yet a fully fledged engineer in the eyes of his CBS employers.

"I knew this A&R guy, Robin Blanchflower,” Humphrey recalls. "He phoned me on the Wednesday and asked, 'What are you doing at the weekend?' I said, 'I don't know,' to which he said, 'Right, I've just signed this band called the Clash. I don't know what they've got, but they've got something. I'll send them 'round now to say hello and then on Saturday and Sunday you'll record and mix two tracks for the A and B sides of a single.' Robin never came to the studio, I never had to play him a rough mix and there were no demos. They just pressed the record, stuck it out two weeks later and it went straight onto the chart.”

That was in March 1977, when 'White Riot' peaked at number 34 in the UK.

"No one was more amazed than the record company,” Humphrey continues. "It had no idea what it had unleashed at that point. It was incredible, and I think I got the job because I was the youngest engineer. As such, I was the least cynical engineer at the Whitfield Street studio; less likely to complain and more willing to indulge the band members. The biggest fear they had was that someone would come along and stick on harmonies or mix the record in such a way that it would sound cute when they wanted it to sound angry. They just wanted it done, and the record company, to its credit, gave them free rein with that initial record and their first album.”

Two Guitars Better

Reportedly produced on a £4000 budget, The Clash was recorded in February 1977 over the course of — as Humphrey now recalls — between eight to 10 days before another three were spent on the mix.

"Joe didn't show much enthusiasm for overdubbing,” Humphrey says. "His vocals largely consisted of single takes, he played his guitar live on the backing tracks and there was very little fixing of the bass. When we put a track down, the drums, bass and two guitars were played live and they mostly would have been retained. However, the person who very quickly learned the art of overdubbing was Mick. He was the one who clocked that you could drop in and out, double track and add other guitar parts. Of course, he didn't tell me he'd been in another band, recorded before and probably knew this stuff anyway, but I got the sense that, over the course of recording the Clash album, he really got into the concept of layering guitars and what that could do to the sound of the record. As a result, it was embellished more by his work than by anyone else's.

"Mick started to use other guitars and other amps while looking for other sounds. He was interested in what the studio could do in terms of tracking. From my perspective, that was dangerously close to going away from the original philosophy of it all being totally raw. But then, everybody knows that, most of the time, two guitars are going to sound a lot better than one, so it didn't make sense to tell Mick, 'Hold on a minute, you said we couldn't do this because Abba double-tracked guitars.' Once he understood that more guitars made a louder record, we went in that direction and he more or less took over the production by making the studio a creative space.”

Joe Strummer and Mick Jones wrote and composed 12 of the 14 tracks that appeared on the UK release of the Clash's eponymous debut album. The exceptions were 'What's My Name?' which they had co-written with Keith Levene and the reggae number 'Police & Thieves', recorded by falsetto singer Junior Murvin in 1976 after he had written it with producer Lee 'Scratch' Perry.

"The Clash were very well rehearsed,” Simon Humphrey continues. "Aside from 'Police & Thieves', all of the songs ranged from under two minutes in length to just over three minutes and they had them down pat. Joe and Mick were feverishly writing lyrics in the studio — most of the songs' lyrics had already been half-written and they were knocking them out on a daily basis. However, the music was pretty well rehearsed, the songs went down quickly, and although a lot has been said about Mick Jones playing the bass instead of Paul Simonon, I can absolutely assure everybody that Paul played all of the bass and that Mick just taught him some of the parts.

"Mick was a pretty competent guitarist by that time. He knew what he was doing. He was the musical side of the band and none of them were amateurs. For his part, Terry Chimes did a perfectly good job, but I don't think I really did him any favours in terms of the drum sound. When I listen to the record, the drums are quite lightweight, and that's partly because of Terry's kit and me being told to not do anything special to it, and it's also because it was quite obvious that he was more a session man than a member of the band. So, he was just doing his job before Topper Headon came in and really crystallised everything by giving the Clash a different sound. It's not that Terry was a lesser drummer; it's just that Topper came in with an attitude and helped everything step up a gear.”

Departing the Clash soon after the sessions for the album ended, Terry Chimes wasn't featured in its front-cover photo — taken in an alleyway facing the band's Camden rehearsal studio — and was acerbically credited as 'Tory Crimes' for his efforts. Meanwhile, the back-cover photo of charging police officers was taken during the August '76 Notting Hill Carnival insurrection that inspired 'White Riot'; a song that was accorded different recordings for the versions that were issued on the album and as a single; the former (running time 1:55) commencing with Mick Jones' "one-two-three-four” count-in, the latter (running time 1:58) with a police siren grabbed from a BBC sound-effects record. Ditto the subsequent, anarchic sounds of an alarm bell and breaking glass, while that of stomping feet was contributed by assorted friends in the studio.

"When I engineered the single — the first recording that I did with the Clash — I didn't know that they had already recorded another version at the National Film & Television School in Beaconsfield,” says Humphrey. "That live version, which had been recorded on eight-track for a very early video, was the one that they decided they wanted on the album, even though the record company would have never put it out as a single because it was terrible in terms of its technical quality and the band agreed. I think it was just one of those punk/New Wave ideas to give the fans value for money... Or maybe they were just trying to be perverse, undermining the record company, because they did genuinely say, 'God, this sounds a bit ropey.' It was below demo quality. In the punk spirit, it was a case of 'This is what we sounded like when we went to the film studio,' and so I remixed it for the album to try to bring it up to spec. It was so horrible, it perfectly suited punk.”

Prog Off

Recorded and mixed within three days along with the non-album B-side '1977', the single version of 'White Riot' also appeared on the altogether different 1979 North American release of The Clash, issued after the band's second album Give 'Em Enough Rope. This was in the wake of CBS deciding that the original UK album, despite reaching number 12 on the chart following its 8th April 1977 release, was too raw and unsophisticated to garner radio airplay in the US... only to see it become the best-selling import of the year there with sales of more than 100,000 copies.

"Having had no previous affiliation to punk, working with the Clash was a real education for me,” says Simon Humphrey whose other credits include anyone from the Vibrators, XTC, Tom Verlaine and David Byrne to Culture Club, the Beach Boys, Bros and Smokie, and who now resides in Yorkshire, where he is resident producer at the ChairWorks studio complex and delivers music production lectures at the University Of Leeds. "Once I saw what was possible with the band, a light went on in my head and I thought, 'Blimey, maybe all this prog rock stuff that I love is a load of bollocks. The Clash were the total antithesis of that and I could have easily recoiled from working with them, but fortunately I just got on with it. I respected them, and I think I really contributed to that first album by not screwing it up for them whereas a lot of other people probably would have done.”