Sade, plus a selection of percussion, photographed in the Power Plant in 1985. Photo: Gered Mankowitz / Redferns

Sade, plus a selection of percussion, photographed in the Power Plant in 1985. Photo: Gered Mankowitz / Redferns

Sade's ice-cool vocals and sophisticated, jazz-tinged instrumentation defined a new kind of soul music for the '80s. Engineer and producer Mike Pela describes the organic recording process that produced one of the singer's most memorable hits.

Helen Folasade Adu helped redefine urban soul when, as Sade, the Nigerian-born Londoner burst onto the scene in the mid-'80s with her multi-platinum debut album Diamond Life. Her laid-back, near-emotionless vocal delivery served as a perfect counterpoint to the high-passion, heavily embellished singing of an Aretha Franklin or a Whitney Houston. Recorded by 'production engineer' Mike Pela and featuring the contributions of Sade bandmates Stuart Matthewman (guitar/sax), Paul Denman (bass) and Andrew Hale (keyboards), Diamond Life was produced with a slick, quasi-jazz feel by Robin Millar at his own Power Plant facility in North-West London. It spent 98 weeks on the UK charts, 81 weeks on the Billboard Top 200, and spawned the hit singles 'Your Love Is King', 'Hang On To Your Love' and 'Smooth Operator' while earning Sade a Grammy Award for Best New Artist.

Between February and August 1985 the same team then reassembled for Sade's even more successful follow-up Promise, which was co-produced by her, Robin Millar, Mike Pela and, in a less central role, Ben Rogan. The album contained such radio-friendly hits as 'Is It A Crime', 'Never As Good As The First Time' and 'The Sweetest Taboo', the artist's signature song which enjoyed a six-month run on the American pop charts.

Power Trip

Mike Pela had started his career at De Lane Lea (now CTS) Studios in the mid-'70s, assisting on the Who's Tommy soundtrack, ELO's Eldorado album and Roy Wood's Mustard (he and engineer Dick Plant donned gorilla suits when performing the single 'Are You Ready To Rock?' with Wood on Top Of The Pops), before going freelance in 1979 and then doing a lot of work at Pete Townshend's Eel Pie facility in London's West End, including Townshend's own Scoop double album (1983) and recordings by John Cougar Mellencamp, Stephen Stills and Generation X.

After teaming up with Robin Millar at the Power Plant in 1983, Pela became the studio's de facto chief engineer until 1991, producing and/or pushing the faders on records by Everything But The Girl, Fine Young Cannibals, Tom Robinson, the Kane Gang, Was (Not Was) and Boy George. Having co-produced and engineered Sade's Stronger Than Pride in 1988, he has since fulfilled the same roles on her Love Deluxe (1992), Lovers Rock (2000) and Lovers Live (2002) while working with the likes of Dreams Come True, Maxwell, Savage Garden, Lorenza Ponce, Erasure and, most recently, Jewel, soul singer Lemar and an as-yet-unsigned girl band named Frendze. The latter were recorded in his home setup comprising a Pro Tools HD, Digidesign Command 8 MIDI control surface, Emu Vintage Keys, Kurzweil K2000, Roland JV1080, Akai S1000 and assorted guitars. Producer Robin Millar with Mike Pela outside the Power Plant, shortly after the recording of the Promise album.Photo: Barry Marsden

Producer Robin Millar with Mike Pela outside the Power Plant, shortly after the recording of the Promise album.Photo: Barry Marsden

Getting The Basics Down

'The Sweetest Taboo' was created in Power Plant's Studio One, where a 30 x 25 x 18-foot live area was complemented by a 36-channel Harrison Series 24 console, Urei 813B main monitors and a 24-track Studer A820 recorder running Ampex tape at 30ips. "We had Urei monitors in all of the rooms so that there was some continuity," Pela explains, "and we also had Acoustic Research AR18Ss, which we discovered at that studio and which I've still got a pair of. They were like hi-fi speakers, they only cost about 80 quid, and once we'd started using them the company stopped making them. They were really nice and natural-sounding, not designed to carry super-low heavy frequencies, but absolutely fine.

"The control room was long and thin, with a large window to the right of the console overlooking the main recording area, which was about two storeys high and had a few screens suspended from the ceiling to break things up. It was quite a good-sized room, with one end slightly under the control room, and it was live but not too live. That was an era when people liked live rooms. Meanwhile, the tape machine was located at the back of the control room as you came up the stairs from the studio, and I have to say it was quite a good discipline being forced to record everything on 23 tracks while allowing for the timecode."

Although some of the Promise sessions took place during a two-week sojourn in Provence, utilising an SSL E-series console housed at the barn-shaped, concrete-built Studio Miraval, it was at the Power Plant where the project commenced in February 1985 and ended seven months later, with the mix being done in the Gallery (Studio Three) located on the top floor, with its 44-channel Harrison MR3. Indeed, Studio One is where the production team initially listened to several of the songs in demo form, although Mike Pela was at the Royal Albert Hall when he first heard one of the new tracks.

Mike Pela at the Power Plant's Harrison desk.Photo: Barry Marsden"The band was on tour and performing 'Is It A Crime', and I thought it was fantastic," he says. "A real, epic torch song that clearly communicated these musicians were capable of more. I subsequently thought the new album also had this epic quality, because they were stretching out a bit and some of the songs were longer as well as quite soulful and intimate. The first album had been recorded pretty much live and the second one was, too, although we began to use the technology more, sampling drums by way of an AMS with a lock-in feature. Everyone appeared to be discovering that at the same time — 'Ooh, look what you can do with this!' Anyone who didn't have a Fairlight was fiddling around with an AMS.

Mike Pela at the Power Plant's Harrison desk.Photo: Barry Marsden"The band was on tour and performing 'Is It A Crime', and I thought it was fantastic," he says. "A real, epic torch song that clearly communicated these musicians were capable of more. I subsequently thought the new album also had this epic quality, because they were stretching out a bit and some of the songs were longer as well as quite soulful and intimate. The first album had been recorded pretty much live and the second one was, too, although we began to use the technology more, sampling drums by way of an AMS with a lock-in feature. Everyone appeared to be discovering that at the same time — 'Ooh, look what you can do with this!' Anyone who didn't have a Fairlight was fiddling around with an AMS.

"Everything was set up for live recording, with plenty of screening and separation between instruments in order to control the dynamics before we'd replace and touch things up later. Dave Early's drum kit was in the far-left corner of the studio, with an AKG D12 on the kick, a Neumann KM84 and Shure SM57 on the snare, an 84 on the hi-hat, a mixture of 57s and Sennheiser MD421s on the toms, a PZM up against each wall in that corner and a Neumann U47 overhead. As it happens, we took the toms off the kit for 'The Sweetest Taboo', and there was also no hi-hat on the track because we didn't think it was necessary — the drum part was very stylised.

"Paul Denman, whose bass was usually DI'd for the definition, stood in front of the drums — he also had a miked amp in the stairwell on the opposite side of the room, but the DI was used for 'Sweetest Taboo' — and next to him was Martin Ditcham, whose percussion instruments were surrounded by corrugated metal screens. Then again, some of the percussion also came from samples on an Emulator II — there's a sort of sticky bongo sound on the choruses which was a sampled pattern that I triggered from the kick drum track. Each trigger would restart the sample, and I experimented with mutes on the kick drum to change the part and recorded the result, mixing onto the Studer A820."

Squashing The Instruments

"Martin Ditcham was known to be a little bit accident-prone while playing, and I remember suddenly hearing a thump during the recording of 'Is It A Crime' thanks to him tripping over one of the corrugated screens and causing it to fall onto a piano stool and flatten the Selmer sax that Stuart Matthewman was about to play. Martin was mortally apologetic while Stuart was saying 'No, it's all right,' through gritted teeth — he quickly had to fetch another sax from home before eventually getting the damaged one lovingly re-hammered."

When Matthewman wasn't blowing on the sax he was standing in the far right corner of the studio, playing either a Hofner acoustic or his Fender Squire, going through a Roland Jazz combo that was close-miked with a Neumann U87.

"The piano, which was about halfway up on the right side of the room, was miked with a couple of 87s and positioned next to a Rhodes, Emulator II and a Hammond B3," Pela continues. "Andrew Hale played a lot of Rhodes on the first album and he tended to use more DX7 on Promise just because he could do more with it."

Sade, who would later re-record her parts in the control room, initially laid down guide vocals in the studio while the band played live.

"At the start of the project we recorded the rhythm section for most of the tracks," Pela explains, "and then there was a long period in the middle when we overdubbed each of the parts, including the vocals. The band's approach was slightly impressionistic, building a track to create a sort of soundscape by just filling in and trying different things. And they didn't always go for the most obvious things — while trying to find something more interesting, more personal to bring out in the songs, there'd be a fair amount of experimentation, maybe playing a part and just using a little bit of it.

"What I like to do is home in on quirky little things that can arise when people run through material without really thinking about what they're doing — I might think 'Hmm, that's good. Let's use that every eighth bar.' Aside from the AMS we had limited sampling, but we'd pick out parts to play again and there was, therefore, a certain amount of inbuilt quirkiness, partly thanks to the way that Robin and I like to work and partly due to the direction in which the band was going. As I've said, we tried to stretch out and experiment, although with just 24 tracks we couldn't experiment too much. We had to get stuff down."

The layout of Power Plant Studio One for the band sessions that formed the basis of 'The Sweetest Taboo'.

The layout of Power Plant Studio One for the band sessions that formed the basis of 'The Sweetest Taboo'.

The Sweetest Vocal

Standing behind a corrugated metal screen at the back of the control room, Sade recorded her overdubbed vocals through a Neumann U87 treated with a delayed EMT 140 echo plate, Dbx 160X compressor and, for the middle section of 'The Sweetest Taboo', an AMS RMX reverb. "We almost always used either an 87, a 57 or a 58 for Sade," says Mike Pela, "and we'd always come back and try other things. In fact, on her most recent album we used a Neumann 49. She's pretty easy to record, although how she approaches the vocals depends on whether or not she's writing the song as she goes along. Although the band typically comes into the studio with some of the songs already written, others will be written on the spot, drawing on ideas that have already been knocking around. So, if Sade is piecing the words together, her vocal will be recorded in sections until she comes up with what she wants, including the right kind of melodic rise and fall. In the case of 'The Sweetest Taboo', on the other hand, her vocal went down in complete takes. And as I don't like too much piecing together, I usually try to keep the number of takes down.

"Before Pro Tools came in, I got into this thing of just recording an artist — when he or she was up for it — on one track, and just dropping in on that so they could hear exactly what was going on and I wouldn't have to end up comping. One time there was this big disaster when I was working with a Japanese band and comped an entire album's worth of vocals. It was just day after day of comping, and I thought it was madness.

"Sade is confident as a vocalist, but she is also quite picky about pitching, so sometimes she can be more sensitive than other people. She thinks her pitching is a weakness, although I don't consider it to be much of a problem — a song will be fine and for some reason she just won't like it. Like most good singers she always has a sense as to whether or not she can improve on a vocal, but we also try to avoid doing too many takes. When she's writing she likes to try different options — even though her vocal might be great and she'll agree to keep it, if she thinks she can get something else out of a song she'll also be quite happy to go back and look for that. She likes getting it right, and in a way she's quite precise, but it's also very much about feel.

"For 'Taboo' she laid down a lovely vocal — it was quite breathy — and then we built up sections, like the middle section where she sings 'I'd do anything for you, I'd stand out in the rain.' That was a case of needing something a bit more rhythmic to fill eight bars of blank canvas, and one of Sade's strengths is that she's always capable of pulling out things you'd never think of. She'd done all that by the time we eventually moved upstairs to the Gallery to do the mix."

Sharing The Duties

In terms of the co-production roles, Robin Millar largely directed operations, saying "Let's do this next," or "Let's try that," while also overlapping with Mike Pela when deciding what sounded good, where a song should be heading and how to best achieve this. "I had a fair amount of input on the artistic side," Pela says, "and the band members were also pretty vocal and quite involved. For her part, Sade liked to be inspired by a song, so while she'd be particularly interested in building up her vocals, she would also comment if there was something she thought should be added or removed. She was right in the middle of everything."

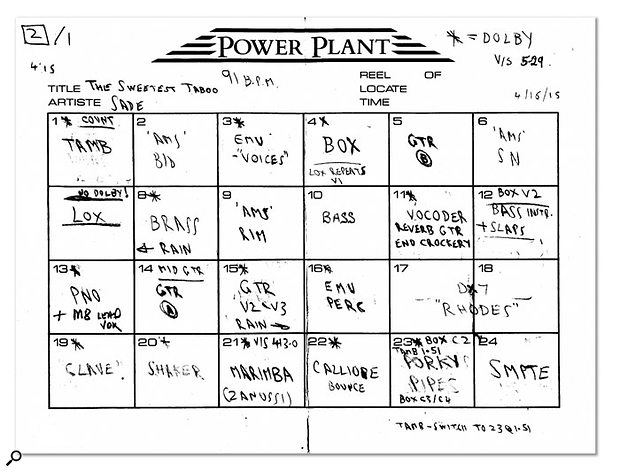

'The Sweetest Taboo' started life as a drum loop that Martin Ditcham created on a Yamaha RX11 and introduced with a basic chord sequence to his fellow musicians. They then routined this, shaped it into a basic song with an 'A' section and a 'B' section, and brought it into the studio for Millar, Pela and Sade to enhance the structure and the arrangement. The original track sheet for 'The Sweetest Taboo'.

The original track sheet for 'The Sweetest Taboo'.

"Generally, if Sade heard something that she liked and thought she could write to, she and the other musicians would keep going with it," Pela remarks. "You see, one interesting aspect to Sade's music is that it is a band effort, not just her, and the result is that there's always continuity and depth. It's not just about a solo artist. They'll come up with ideas, she'll find something she likes and then that will turn into a song. That's the way things have always developed, and that is one of her strengths. It isn't just her. I mean, she's obviously unique and instantly recognisable, which is great, but she also has this support behind her, and that, too, is great. That's the musical continuity. All of them have been together through thick and thin, and that is slightly unusual and, in terms of the public perspective, maybe a bit under-appreciated.

"'The Sweetest Taboo' has a middle section that comes back at the end, so the basis of the song is quite simple, and the original idea was that we were going to use this rhythm provided by the drum loop. Dave Early, however, wanted to play it, and it would have been a bit silly to do that with a sampled rim and snare going on at the same time, so he played it as part of the live band and then we dropped in on that drum track to enhance the live feel, sampling the rim, the snare and the kick to get a constant dynamic, a constant punch to the drums. At the time we were doing this sort of hybrid thing that was suddenly becoming available for people to try out.

"Having created the drum track, we then pieced the song together bit by bit. The bass was a deceptively simple part, which is really Paul Denman's trademark, and he played that in the control room, providing us with a totally rock-solid but live groove. The band, you see, had a kind of in-built sound, and as soon as Sade sang, that sound became instantly recognisable. There was no concerted effort to repeat the formula of the first album. The sound just evolved in the hands of the musicians and without much involvement from the record company which was so grateful for its artist's supposed 'overnight' success after years of struggle. That's why, even though some company representatives came down to the studio, they never dictated how things should be. They knew that Sade shied away from obviously commercial material, and that on this album she and the other musicians were more interested in stretching the songs out and taking the opportunity to play around a bit. That having been said, 'Taboo' was structurally quite tight and from the start it did sound like it would be a single."

Tickling The Ear

Meanwhile, it was a sampled four-bar acoustic guitar pattern played by Stuart Matthewman that underpinned 'The Sweetest Taboo'. "We put it in the AMS and triggered it from the drums," Pela explains, "and because the drums were actually live we had to move the sample about a bit by changing its start time, trimming the front of the sample so that it would fit in properly on certain bars. This meant there was some rather crude editing going on, with us doing whatever it took to get to the end. Sometimes you're not aware of these challenges until they're upon you — a case of 'Oh yeah, we'll just sample that and insert it there,' and then it's like 'Ah, OK, now we do have a bit of a problem. We'll have to do this and that. How long is it gonna take?' Suddenly you realise you're in the middle of something and you've just got to deliver it. Nowadays, of course, that kind of thing is so easy, but back then it really wasn't."

Mike Pela today.Following the recording of drums, bass, guitars and keyboards, brass swells were performed for the song's middle section courtesy of Stuart Matthewman on tenor sax, Terry Bailey on trumpet and Pete Beachill on trombone. Matthewman also played trademark picky electric guitar on the choruses, an extra track of bass slaps was recorded and treated with a roomy reverb for extra dynamics, and Martin Ditcham laid down cabasas and a solid shaker part that runs throughout the song; all part of the detail and texture that belie the number's apparent simplicity.

Mike Pela today.Following the recording of drums, bass, guitars and keyboards, brass swells were performed for the song's middle section courtesy of Stuart Matthewman on tenor sax, Terry Bailey on trumpet and Pete Beachill on trombone. Matthewman also played trademark picky electric guitar on the choruses, an extra track of bass slaps was recorded and treated with a roomy reverb for extra dynamics, and Martin Ditcham laid down cabasas and a solid shaker part that runs throughout the song; all part of the detail and texture that belie the number's apparent simplicity.

"On the chorus there were some half-spoken lines going through a vocoder," says Pela. "Some marimba and high Emulator voice-pad-type things, as well as a few low piano notes in the verses and some weird percussion sounds that you can hear towards the end of the song — Martin [Ditcham] and Dave [Early] were in the studio, both sitting at cafe-type tables, and Dave was blowing across the top of a bottle [referred to as 'porky pipes' on the song's track sheet] while Martin was tapping on a couple of glasses with a fork, all miked with a pair of 87s facing away from one another. The two of them were hyperventilating, falling about laughing, and we had to gate out a lot of their laughter. This went down live, without any sampling, and it worked really well on the track, as did some rain on the intro and outro that came from a sound-effects record, and the thunder that we created by turning up the reverb on a Roland amp and dropping it gently from a couple of inches off the ground. The coils were all twanging, so it was definitely an impressionistic type of thunder, whereas when the band toured they used actual thunder sound effects.

"There was no master plan to any of this. We'd just try things out and keep bits of them, and as a result there are always little things coming in and out of the mix, tickling the ear. You can't quite take it all in at once. It's basically simple but it's also deceptive, because there is actually a lot going on, and every time you listen to it you hear something else. Everything is there for a reason."

Hanging In The Gallery

Like the other tracks, 'The Sweetest Taboo' was mixed in the Power Plant's Studio Three, known as the Gallery. "The Harrison MR3 in there was a lovely, warm, sweet-sounding board, and we had this Mastermix automation which was a stand-alone unit hooked up to the console. It took big five-inch floppy disks, and from what I can remember you could keep four passes. However, occasionally this thing would also go nuts and it would lose data or stop altogether. So, it wasn't 100 percent reliable, but it certainly did the job even if there were a few times when it basically blew up, causing the gnashing of teeth and pulling out of hair. I mixed on to Studer A820 at 30ips, and also to Sony F1. I used the little speaker on the Studer as an additional mono mix reference, and we had a Roberts radio simulator that was based on a traditional portable radio with different compression/EQ settings to simulate different broadcast types.

"I like to ride the effects during the mix, especially on the vocals, playing the desk like an instrument. That way you only hear them when you want to, instead of just filling in the sound. And on Promise, since we weren't doing recalls each time we moved from one track to another for overdubbing, when we got into the mix we were basically starting again. For instance, there was a quarter-beat delay on the rim, and I was looking to lock the rhythm into a hypnotic groove while using reverbs to give the whole thing a 3D depth, much more so than if I was doing it now. Nevertheless, on the whole I think the Sade recordings have stood the test of time quite well. They haven't really dated, and while that's partly due to luck, her music has always had that timeless kind of feel to it.

"In all, we worked on 'Taboo' for six or seven days, and then we went back and poked it a bit more towards the end of the project because there had to be a 12-inch and a seven-inch edit. I had a lot of fun with the mix because it was a good-sounding track. It was straightforward but with a lot of detail, and I do remember finishing it off just as the sun came up over Willesden. A lovely sight!"