Originally intended for another group, 'Kiss' was quickly reclaimed by Prince when he heard David Z's arrangement. Despite record company scepticism, the track became his third number one single and rejuvenated his career.

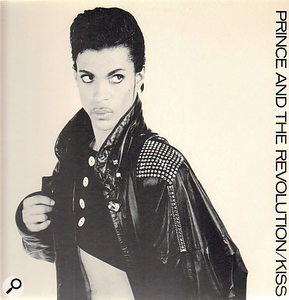

Prince on stage, 1986.Photo: Photoshot/Shooting Star

Prince on stage, 1986.Photo: Photoshot/Shooting Star

Prince is very competitive and I think that's a driving force,” says David Z. "The competition factor drives him on and on and on. He wants to be better than the next person and he often succeeds at achieving that. I remember when Madonna got a $60 million record deal. Everybody was in awe, and Prince was walking around, going, '$60 million? Shit! I'm gonna get a $90 million record deal!' That's the kind of competitive spirit he has. He's got more energy than anybody. I'd get calls at two in the morning to come into the studio and work. He's nonstop.”

From A To Z

David Z is, arguably, best known for his work with the multi-talented, Minneapolis-based artist, ranging from the live 1983 recording of his signature song 'Purple Rain' to the arrangement and engineering of the iconic 'Kiss' which, following its February 1986 release, peaked at number six in the UK and became Prince's third American number one. Nevertheless, Z does have a far more extensive track record: engineering and playing guitar on Lipps Inc's 1980 transatlantic disco smash 'Funkytown', producing and engineering the Fine Young Cannibals 1988 US chart topper 'She Drives Me Crazy', and earning production, engineering, instrumental and/or compositional credits for, among others, Sheila E, Jermaine Jackson, Jody Watley, The BoDeans, Buddy Guy, A-ha, Etta James, Joe Cocker, John Mayall and Jonny Lang.

Born David Rivkin in Minneapolis, Minnesota, Z played guitar in various local rock bands as a teenager and eventually landed a job there as a promotions man for A&M Records. Then, in 1968, after complaining to the company about the quality of records he was expected to push to radio stations, he was told by his LA boss, "If you think you can do better, pack your bags, get in your car and move out here.”

This is what Z did, and soon thereafter he was also signed to A&M as a songwriter. This and his skill as a guitarist came in handy during the next five years, which saw him play on records by the likes of Billy Preston, while earning a co-composer credit with Gram Parsons on his debut album GP for the track 'How Much I've Lied'.

"It was like going to school,” Z says. "I didn't really know all that much before leaving Minneapolis. However, I high-tailed it back there after Gram Parsons died. Those were the days of the hippie movement, drugs and free love, and I needed to return to some sense of normalcy.”

Sunset Sound's Studio 2 was often the venue for Prince sessions and was also where the Mazarati version of 'Kiss' was recorded. Photo: Hannes BiegerIn Minneapolis, as a means of surviving in the music business, David Z arranged with a local booking agent to cut band demos at ASI Studios, in order to secure the bands local club gigs.

Sunset Sound's Studio 2 was often the venue for Prince sessions and was also where the Mazarati version of 'Kiss' was recorded. Photo: Hannes BiegerIn Minneapolis, as a means of surviving in the music business, David Z arranged with a local booking agent to cut band demos at ASI Studios, in order to secure the bands local club gigs.

"I just attended the sessions,” he recalls. "However, during the course of my doing that, the engineer at ASI said, 'I'm sick of doing this. Why don't you do it?' I told him, 'I don't know how in hell to do that. I'm a guitar player and a songwriter.' Still, he put me in there and pretty much locked the door for two years, during which time I read all the books I could about how to engineer and make the equipment — a custom console and an eight-track machine — work, because I was never really schooled in that.

"In 1975, a friend of mine was backing a group called Grand Central, and brought it into ASI to cut a demo. The band members consisted of 16-year-old Prince, André Cymone on bass guitar and Morris Day on drums, and although they sounded decent nothing really happened as a result of that demo. In fact, nothing was really happening at all in Minneapolis and [twin city] St Paul in terms of the music business back then. The record company execs wouldn't even come up there — they thought we had buffalo in our back yard — and so it was a pretty frustrated musical community. For decades, all everybody had been saying there was 'We need a hit', and to achieve, that everyone from Bob Dylan to [bassist] Willie Weeks had left.”

Fast-forward to a year later, by which time David Z was working at another local facility, Studio 80, where in December of '74 Dylan had done some of the recordings for his classic album Blood On The Tracks. Prince was now being managed as a solo artist by another of David Z's friends, Owen Husney, who turned up at Sound 80 with a tape of his protegé's songs.

"We listened to them and I thought they were really good,” Z recalls. "Those songs would end up on Prince's first record.”

DIY

With David Z engineering, Prince subsequently set about single-handedly recording demos of three 12-minute tracks at Sound 80: 'Soft & Wet', 'Baby' and 'Make It Through The Storm'.

"In advance of each session, he used a little hand-held cassette recorder to hum the bass, guitar, keyboard and synth-produced horn parts, and he also mouthed the beats,” says Z. "I set up a station for each instrument and, using the cassette machine to remind himself what to do, Prince played every single part. It was amazing to me, because that's pretty hard to do while retaining your objectivity. However, right from the start he was great; the complete package from the first minute I heard him. He did nothing but eat, sleep and make music, and to this day I'm sure he doesn't sleep much. He had more energy than anybody.

"My cousin Cliff Siegel, who was a regional promotions man for Warner Brothers, took the three songs we had recorded to his boss Russ Thyret, and he in turn took it to [A&R exec] Lenny Waronker, who absolutely flipped. He couldn't believe this kid was doing everything.”

Indeed, titled For You, Prince's debut album would not only be produced and arranged by him, but it would also feature his own compositions, as well as his playing of all 27 instruments.

"Before Warner Brothers signed him, Prince, Owen and I flew out to LA for them to see if he really did do everything himself,” David Z explains. "When we got to the Warners studio, Lenny Waronker was there with [producers] Russ Titleman, Gary Katz and Ted Templeman, and I think they were trying to decide who would produce the first record, even though Owen had already demanded that Prince produce himself. Well, to recreate the demo, we did a session where Prince played all of the instruments and performed the vocals, and once they saw that they went, 'OK, he can do it.'

"Back then, I was just a beginner and Warners wanted a reputable engineer to work on the first album. So I got the guy who used to cut my songwriting demos at A&M, Tommy Vicari, and later on Prince then had me fly out to the Record Plant in Sausalito to record his vocals.”

This was after, having learned all he felt he needed to know about engineering by observing Vicari, Prince had edged him out of the picture.

David Z at Prince's Paisley Park facility with artist Vaughn Penn back in the mid-1980s."He really over-produced that first record,” says David Z. "He put ten million vocals on there...”

David Z at Prince's Paisley Park facility with artist Vaughn Penn back in the mid-1980s."He really over-produced that first record,” says David Z. "He put ten million vocals on there...”

The title track actually required 46 vocal overdubs, but who's counting?

"We stacked them and stacked them, including all of the background vocals,” Z continues. "It was an experiment. We were all experimenting.”

Once the For You album was in the can, the main man had to assemble a band with which to tour in support of his debut record.

"Prince had never played live with a band and so the heat was on,” says Z. "His idols Sly Stone and Jimi Hendrix both had bi-racial mixes in their own groups, and the fact that Prince wanted to tap into the same sort of thing was great because not many people, either black or white, were doing that at the time. Prince wasn't Motown, he wasn't Philly, he was his own thing.

"My younger brother Bobby, who worked for Owen Husney as a runner, had been a drummer in a couple of groups and we had played together a lot. So Prince took him on, along with André Cymone on bass, while holding open auditions for the other band members.”

Time Out

David Z wasn't involved in any more studio sessions with Prince until those in 1982 for 'Delirious', the third single off his fifth album, 1999. Then, in August the following year, at the First Avenue nightclub in Minneapolis, Z recorded a benefit concert by Prince and his sidekicks — now named The Revolution and featuring the debut of guitarist Wendy Melvoin — to aid the Minnesota Dance Theatre. For this, he utilised the 'Black Truck' mobile unit from New York's Record Plant, capturing the 70-minute performance from which three songs were extracted for the soundtrack to Prince's 1984 film Purple Rain: 'I Would Die 4 U', 'Baby I'm A Star' and the title number. These would be the closing tracks on the album.

In its full form, with Prince playing his Hohner Telecaster copy instead of the Cloud guitar that he used in the movie and on the subsequent tour, 'Purple Rain' lasted 13 minutes, 20 seconds. However, an extended introductory guitar solo, second chorus and third verse were cut to create the 8:41 version that, commencing about three minutes and 50 seconds into the live performance, ended up on the album with the entire first verse, chorus and second verse intact. The song was further shortened to 4:05 for the single.

"The only real overdubs were the string section and replacing the bass,” comments Z, with regard to the studio sessions that took place without his own involvement at LA's Sunset Sound during August and September of '83. "Prince's concert vocal was used for the record, including the echo that I produced on the board. It's pretty cool.”

Released in September 1984, 'Purple Rain' climbed to number two in the US and the UK, following up on the success of the two preceding singles from the same album, 'When Doves Cry' and 'Let's Go Crazy'. The former, which was Prince's first American chart-topper, broke with dance-song tradition by having no bass line, and in April 1985 he repeated this ploy for the stripped-down, in-your-face funk of 'Kiss'.

The Mazarati Version

"For a long time, Prince had been talking about forming his own record label,” says David Z, who by then was heavily into the creative employment of sampling, synths, loops and drum machines that had already become characteristic of that era. "One day, he called me and said, 'There's a group that I've just signed and want you to have something to do with. Come to LA.' So, I went there, walked into Sunset Sound, and he said, 'You're going to produce this group called Mazarati.' That was the first time I'd been labelled a producer, which I'm very grateful for. It got me started.”

Formed by the Revolution's bassist Mark Brown (aka Brown Mark), Mazarati was a funk/R&B outfit whose only hit was the Z-produced/Prince-co-written '100 MPH', but whose greatest claim to fame was a recording that never saw the light of day — at least, not in the form that the band members intended.

"We did a bunch of songs for Mazarati's album,” Z recalls. "Then, when we needed a single, Prince gave me this demo of him just playing straight chords on an acoustic guitar — one verse and one chorus — while singing in a normal pitch; not the falsetto that's on the finished record. To us, it sounded like a folk song and we were wondering what we could do with it. No way was it funky. Anyway, starting with a LinnDrum, I programmed the beat and began experimenting. Taking a hi-hat from the drum machine, I ran it through a delay unit and switched between input and output and in the middle. That created a very funky rhythm. Then I took an acoustic guitar, played these open chords and gated that to the hi-hat trigger. The result was a really unique rhythm that was unbelievably funky but also impossible to actually play... I'm sure that sound influenced the fabulous new Daft Punk song 'Get Lucky', because it uses the same trick, with the guitar gated to some sort of rhythm and sequencer.

"Next, I remembered a little piano part from a Bo Diddley song called 'Say Man' and put it on there, and then Tony Christian sang the lead part, an octave lower than what Prince wound up doing. The background vocals I adapted from the Brenda Lee song 'Sweet Nothings' — good music is always taken from somewhere else — and that was that. The whole thing was done in a day.”

Hijacked

Or David Z and the guys in Mazarati thought it was. The fact is, in this form 'Kiss' sounded OK — a so-so dance number. However, Tony Christian's lead vocal was a little soulless and uninspiring, and when Prince heard the track he decided to head in a different direction... with himself at the helm.

"When I came back into the studio the next morning, Prince had already taken it off the machine, replaced the vocal with his own falsetto performance — which, I guess, he felt it needed — got rid of the bass part and added a James Brown 'Papa's Got A Brand New Bag' guitar lick,” Z recalls. "'What happened?' I asked, to which he replied, 'It's too good for you guys. I'm taking it back.'”

Boasting a four-octave range, Prince sang virtually the entire song in head voice, reverting to chest voice for the final line, as well as a single note before the last chorus. "At the time, I think he was into using a [Sennheiser MD] 441,” says Z.

"We only used nine tracks for that song, including a bass drum on one track, the rest of the drums on another and the hi-hat on a separate track. As for the lack of bass guitar, we always ran the kick drum through an [AMS] RMX16 and put it on the Reverse 2 setting to extend the tail of the reverb. That served as a kick drum and a bass, and it was a signature sound that we used all the time with Prince. We didn't need a real bass. And there was no reverb on anything else; just the kick. The guitar was dry and gated, and everything else sounded kind of different to the corporate rock that was on the radio at that time.”

Mazarati's backing vocals ended up on the finished record, yet this was scant compensation for what they had hoped would be their breakout hit.

"They were pissed,” says Z. "Prince had promised everyone a share of the songwriting credit, but that never happened and they were kind of mad about it.”

While Z had engineered the Mazarati recording in Sunset Sound's Neve 8088-equipped Studio 2, Prince used the API/DeMedio-equipped Studio 3 to record his overdubs.

"We had a factory going,” Z says. "I did a bunch of things like that, with him always in the other room. That's also how we worked at Paisley Park.”

According to David Z, the minimalist arrangement of 'Kiss' required him and Prince to spend only "about five minutes doing the mix”. Nevertheless, he wasn't involved with the 12-inch mix, which, built around the funky guitar lick and featuring additional lyrics as well as a more comprehensive arrangement — complete with organ and bass guitar — could be heard in Prince's critically-panned, commercially disappointing 1986 musical-drama movie Under The Cherry Moon, which he directed and starred in.

"The 12-inch was done by Prince after the fact,” Z explains. "He was obligated by the record company to do a dance version, and it was just a matter of editing in eight bars and then another eight bars of something different. Prince did a lot of his own engineering; sitting behind the board and singing, playing guitar or playing bass while punching buttons at the same time. He worked super-fast. And, apart from the first album, that went for everything we did.

"We'd have these stations set up, with drums out in the room, the bass plugged in, the keyboard plugged in, the guitar plugged in, and he'd jump around between stations while expecting everyone to work as super-fast as he did. If someone didn't, there'd be hell to pay; I've seen him be really hard on some second engineers. So we had to be aware of what he was doing and when he wanted it done. He'd jump to the guitar, you'd hit 'record' and bam, it was done.

"There was no rehearsing. I think he just rehearses in his head, 24/7. He'd start a song, do all of the parts, and then we'd mix it and take it off the board before starting another one. We often did two songs a day, and it was usually a constant process of starting a song and totally finishing the song within about fours hours without any coming back to overdub or remix.”

Power Play

The soundtrack album, Parade: Music From The Motion Picture Under The Cherry Moon, was the final record on which Prince was backed by the Revolution. He was reinventing himself, as evidenced by the new image that saw him dispense with his curly mane, purple outfits and ruffled shirts in favour of shorter, slicked-back hair and smoother-looking clothes. Accordingly, 'Kiss' matched the mood of the moment, yet it initially didn't impress the record-company honchos.

"It was so different to everything else out there that the Warner Brothers executives freaked out when they first heard it,” David Z confirms. "I was going to get credit as the producer, arranger, everything, but when I talked to the Warners A&R guy he said, 'Oh man, Prince really screwed up. It sucks.' I thought, what? My heart just hit the floor. He said, 'It sounds like a demo. There's no reverb, there's no bass — it's terrible.'

"I was shaken and really disappointed. At that time, however, Prince had enough power to go, 'That's the single and you're not getting another one until you put it out.' The rest is history. When he recorded 'Kiss', Prince was actually going down in terms of his popularity. He had already hit his peak and people were going, 'Ah, Prince is over with.' Well, that song, because it was so different, totally reignited his career and a year later Warners were trying to sign people who sounded like that.”

By then, Prince's third US chart topper had earned him a Grammy Award for Best R&B Vocal Performance by a Duo or Group. Yet, David Z — who now resides in Burbank, California, and recently produced Cyril Neville, the youngest of the Neville Brothers — didn't crow about this.

"I remember speaking to that A&R guy about other things, but I never cornered him in terms of what he'd said about 'Kiss',” he remarks. "I didn't think it was my place to do that. The proof was in the pudding.”

Paisley Park

Construction of Prince's $10 million Paisley Park studio complex, located in Chanhassen, close to Minneapolis, commenced in January 1986, and the facility opened in September of the following year. Architect Brett Thoeny and acoustician Marshall Long were the main designers.

By the early 1990s, the complex totalled 55,000 square feet and comprised four studios — A, B, C and D — as well as a video editing suite, a 12,500 square-foot sound stage, rehearsal room, production offices and private dressing room. The 1500 square-foot Studio A housed a 48-channel console and then a 64-channel SSL 6000E, Studio C had a 36-input Soundcraft TS24, and Studio D was a small DAW-based facility. The 1000 square-foot Studio B was, as per Prince's specifications, patterned after Studio 3 at LA's Sunset Sound.

"It was the same shape, the same size and had the same board,” recalls David Z, referring to the API/DeMedio 48-channel console with GML moving-fader automation. Other equipment included two Studer A800 Mark III multitrack machines, Studer A820s and a Westlake SM1 five-way monitoring system.

"We loved that Frank DeMedio-modified API board in Studio 3 at Sunset,” says David Z. "It was my favourite. Everyone who's worked there over the years has told them 'Don't change it,' so they haven't. In that control room, the back wall is right behind the engineer's chair, and if you can get it to vibrate, you know you've got it right.

"You can build the same studio somewhere else and if the door isn't facing the right way it isn't going to be the same. However, with Studio 2 at Paisley, Prince managed to build a great room that, I think, was even better than the one at Sunset. It was fantastic. The stuff I did in there still stands up, including the Fine Young Cannibals and Big Head Todd & The Monsters. Studio 2 was mine and I ended up working there for about eight years, bringing in my own business on the strength of people wanting to work at Prince's studio.”