'The Most Beautiful Girl In The World' was one of the defining moments of the Nashville sound, and was the product of a finely-honed studio recording process.

"The song is where it all starts," says Lou Bradley. "Everybody else is along for the ride. You can have the greatest band that plays the greatest music, as well as the best producer, the best engineer and the greatest singer in the world, but if you don't have the right song it's really just a limp noodle. On the other hand, with a great song you can be lacking in all the other categories to some extent and still come up with a good record."

A native of Pensacola, Florida, Bradley began engineering there in the late '50s and early '60s, and followed this with a four-year stint at Bob Richardson and Bill Lowery's Mastersound studio in Atlanta, where he tracked the likes of Joe South, the Classics Four, the Tams and Billy Joe Royal before relocating to Nashville in 1969. There he worked as an in-house engineer at the Columbia Records facility that had previously been owned by legendary country producer Owen Bradley (not related to Lou) and his brother Harold: an army surplus Quonset hut (perhaps better known as a Nissen hut to British readers) attached to a house at 804 16th Avenue, where the famed 'Nashville Sound' was crafted along with the efforts of Chet Atkins and Bob Ferguson over at RCA.

Countrypolitan

Still producing and engineering today for the likes of Merle Haggard, George Jones and Willie Nelson, Lou Bradley enjoyed his halcyon years at Columbia, when he sat behind the board on sessions produced by another Nashville legend, Billy Sherrill, featuring artists such as Johnny Paycheck, George Jones, Tammy Wynette and Charlie Rich.

Charlie Rich and producer Billy Sherrill in Columbia's Studio B: the Quonset hut.Sherrill, who signed these acts to Epic Records, wrote or co-wrote many of their greatest hits — including Wynette's 'Your Good Girl's Gonna Go Bad' and 'Stand By Your Man' — and he was the chief architect of what came to be known as 'countrypolitan'. Successfully targeting the mainstream pop market of the '60s and '70s while earning the scorn of purists, this sub-genre comprised Nashville's traditional fiddles and steel guitars often embellished with vocal choruses and even string sections to create a much larger, more lush sound.

Charlie Rich and producer Billy Sherrill in Columbia's Studio B: the Quonset hut.Sherrill, who signed these acts to Epic Records, wrote or co-wrote many of their greatest hits — including Wynette's 'Your Good Girl's Gonna Go Bad' and 'Stand By Your Man' — and he was the chief architect of what came to be known as 'countrypolitan'. Successfully targeting the mainstream pop market of the '60s and '70s while earning the scorn of purists, this sub-genre comprised Nashville's traditional fiddles and steel guitars often embellished with vocal choruses and even string sections to create a much larger, more lush sound.

"Dynamics were a big part of Billy's philosophy, but most of the time this was to free up the singer, to get the band out of the way of the singer," Bradley explains. "A lot of times Tammy would sing soft, but then when she kicked it in the bridge the band would have to kick it, and Billy was great at figuring that out. I really enjoyed working with him."

Through the early '70s, Sherrill continued to develop the countrypolitan sound via his work with newcomers like 13-year-old singing sensation Tanya Tucker, yet nowhere was it better realised than on the 1973 Behind Closed Doors album of Charlie Rich, an industry veteran who'd enjoyed only sporadic success during the previous two decades with his melding of country, rockabilly, blues, jazz, gospel and soul. Not nearly as eclectic as his prior work, this record nevertheless enabled the so-called Silver Fox to hit it big, thanks to a pair of beautifully arranged, expertly delivered ballads: the country-pop title track, written by Kenny O'Dell, on which the singer pledges his love for a woman with whom he shares his greatest moments, yes, behind closed doors; and 'The Most Beautiful Girl', an exercise in haunting melancholy co-composed by Sherrill with Rory Bourke and Norro Wilson, which has the narrator searching for his lover after she walked out on him when he foolishly opened his mouth.

This song actually dated back to 1968, when Bourke and Wilson wrote it as 'Hey Mister, Did You Happen to See the Most Beautiful Girl in the World?' Then Sherrill got involved and the title was wisely shortened. Indeed, lyrically both numbers were traditional country and western, yet Sherrill's multi-layered arrangements and Rich's soul-tinged vocals were anything but, and the result was international crossover success. While 'Behind Closed Doors' topped the country charts, went Top 20 on the Billboard singles chart and was named Single of the Year by the Country Music Association, 'The Most Beautiful Girl' was a number one US single and also a smash in the UK, contributing to Rich winning a CMA Award as Best Male Vocalist and a Grammy for Best Country Vocal Performance, Male. Behind Closed Doors, certified gold, was also the CMA's Album of the Year.

The Charlie Rich Sound

Rich and Sherrill had first met during the previous decade, when Sherrill was producing and engineering at the Nashville studio of Sun Records founder Sam Phillips, where he became one of the first people in that town to actually record overdubs. Sherrill then signed Rich to Epic in 1967, and over the next few years proceeded to turn him into a smooth, middle-of-the-road balladeer. However, as the singer's finely nuanced performance demonstrated on Behind Closed Doors, he was much more than this, and Sherrill knew it.

Inside the Quonset hut. To the left, behind the piano, you can see the drum booth; the blanket above it is there to absorb some of the drum spill. On the right-hand side is the amp table with its high-backed acoustic screen. Also, note the Altec speakers above the control room.Photo: The Mike Curb Family Foundation"I always enjoyed Charlie's sessions," asserts Bradley. "Boy, he was something else. I don't think I've ever been around an entertainer or any guy who had the sex appeal for women that Charlie Rich did. When he sang a song to women he sold a bunch of records. He was a good guy, and to me he was a joy to work with because he was a real individual.

Inside the Quonset hut. To the left, behind the piano, you can see the drum booth; the blanket above it is there to absorb some of the drum spill. On the right-hand side is the amp table with its high-backed acoustic screen. Also, note the Altec speakers above the control room.Photo: The Mike Curb Family Foundation"I always enjoyed Charlie's sessions," asserts Bradley. "Boy, he was something else. I don't think I've ever been around an entertainer or any guy who had the sex appeal for women that Charlie Rich did. When he sang a song to women he sold a bunch of records. He was a good guy, and to me he was a joy to work with because he was a real individual.

"A lot of times we might do a whole bunch of vocals, about four or five, and Billy was good at mapping this out. It might involve a lot of switching, and if it was inconvenient for me to do this, he'd take care of the switching while I did the mixing. Occasionally he'd also ride the faders: we respected one another, and if he wanted to reach over and grab something I wasn't going to slap his hand. He'd been a great engineer before becoming a producer, and he knew what he was doing.

"I recorded Charlie with a Neumann M49. He had a real full voice, but he made a lot of lip sounds — smacks and clicks — and the spike on the top end of the 49 is smoother than that on the U47 or 87. The 49 got more of the meat of his voice and less of the extraneous sounds, and I also used a Neumann foam pop shield on that mic. We had the old-style cloth shields that I'd use on 47s and 67s, and they were great, they didn't colour the sound, but the foam one worked good on Charlie."

Inside The Quonset Hut

Looking out through the control room window of Columbia's Studio B, the live area layout for these sessions saw Jerry Carrigan's drums in a shed-like booth on the near right side, a low divider separating the drums from Henry Strzelecki's Fender Precision bass guitar and Fender amp that were to the far right, and then, farther left, immediately in front of the drums, another divider that separated the kit from Pig Robbins' piano. This was surrounded by a couple of acoustic guitarists facing one another — one playing straight, the other playing with a high third string — the four Nashville Edition backing vocalists and, as mentioned, the singer himself. Pete Drake played steel guitar, sitting in the center of the room, electric guitarist Billy Sanford was farther to the left, and a Hammond organ and Leslie cabinet were against the far-left wall.

Lou Bradley (left) in the control room with 'Most Beautiful Girl' co-writer, Norro Wilson.Photo: The Mike Curb Family FoundationNeumann U87 microphones served as overheads on drums, while an Electrovoice RE20 was dedicated to the kick, and Neumann KM84s were used for the snare drum and toms. Lou Bradley recalls that when he first began working at Columbia many drummers routinely used the house drum kit.

Lou Bradley (left) in the control room with 'Most Beautiful Girl' co-writer, Norro Wilson.Photo: The Mike Curb Family FoundationNeumann U87 microphones served as overheads on drums, while an Electrovoice RE20 was dedicated to the kick, and Neumann KM84s were used for the snare drum and toms. Lou Bradley recalls that when he first began working at Columbia many drummers routinely used the house drum kit.

"They might just bring their own snare, cymbals and hi-hat," he says. "Jerry Carrigan was a great drummer. He'd put it where the singer wanted to feel it. And Buddy Harmon was great, too. They were both really creative drummers, although in different ways. Carrigan came from more of a blues background, having originally played at Muscle Shoals."

Meanwhile, the acoustic guitars were also recorded with KM84s, another KM84 was placed inside the piano's slightly-open lid, the backing vocalists stood around a U47, and a Neumann M49 was used for the steel guitar, while the bass was recorded both off the pickup and via the output from its amp.

"Henry was one of the best at going from electric to upright, and back and forth," Bradley remarks. "Then again, Bob Moore was a great acoustic player, and he played on 'The Most Beautiful Girl', recorded with an RCA 44. At the same time, we had a table that had been built for the guitar years before, and it had a high back with acoustic tile on the guitar side to stop it getting back over to the vocals. Billy Sanford's amp sat on that table, and it was miked with either a Neumann U67 or 87.

"Aside from playing good licks, Sanford had the knack of always figuring out what to do. A lot of guitarists can play a good lead, but if the song doesn't call for them to do anything they're kind of out to lunch. Sanford would pick around and figure out what he could do to contribute without being in the way. He was always coming up with these little lines that would underlie stuff, and it would all be going down live."

Ex-army Recording Studio

"When I went to work at Columbia in '69, my first chore of duty was to wire up the new 16-track, 24-input console, built by Eric Porterfield and the CBS crew in New York," Lou Bradley recalls. "This had Langevin EQs and faders, just like the original three-track, 12-input Langevin console installed there by Owen. Columbia normally used their own equalisers and faders, so the console they built for Studio B was the only one they ever did that way. The multitrack recording we did went from four to eight to 16 — I wondered why we didn't just start with the Ampex MM1000 16-track. I used the original Dolbys with that machine, which were a great match. For monitors, we had Altec A7s and then went to UREI Time Aligns which also had Altec speakers. We had a four-track monitoring system, so I could hear two A7s and stay in the middle, and I could hear A7s out in the studio, driven by McIntosh amplifiers.

"When I did my first Columbia session, I thought, 'Boy, this place sounds weird compared to what I remember.' I'd been in the control room before when people were playing or setting up the studio, and these big theater curtains had been used in there, high up in the ceiling, to reduce the downward reflections. But then the fire marshall had come in and made them pull all that out. You see, the Quontset hut wasn't all that big, but it also wasn't teeny-weeny small. I once recorded a 39-piece orchestra in there and it was wall-to-wall people. The room was kinda in the middle acoustic-wise. It was not real live, but it was not dead either. The floor was vinyl tile on concrete, and we had some area rugs as well as several dividers. The walls were wood, and on them were panels of old-style acoustical tile, so it would be live and dead, live and dead. I think that's one reason why the sound was fairly neutral. However, since the hut was oval, the sound also wanted to go up and come back down, creating all sorts of problems, and this had been solved early on.

"The walls went up about 12 feet, and there was a framework that formed a rectangle in the middle. Marching down each side were a series of louvres, fixed not adjustable, and they faced ones on the other side that were fixed at a different angle. This changed all the way up and down the room, the idea being to diffuse the sound up into the area above the louvres without those weird reflections coming back down, and it worked. However, when the curtains were removed, the problems returned, so I started climbing up there and clandestinely installing any fibreglass tiles that were lying around, to get things sounding how they did before. It was a great room, and if the musicians wanted to, they could play in there without earphones."

Nashville Sounds

"Billy kinda had a pecking order on guitars and nobody ever said anything about it", says Bradley. "I mean, if Billy Sanford walked in and he saw Jerry Kennedy in the room, he'd go get his acoustic because he knew Jerry was going to play electric. On the other hand, if he walked in and didn't see Jerry, he'd go get his electric, and if Pete Wade walked in and saw the other two he'd go get his acoustic. They knew who Billy hired and they knew what their job was.

"At the same time, Pete Drake was Billy's horn section on steel guitar. If you listen to a whole bunch of Billy Sherrill records, what Pete's doing is what a horn section would do. And I don't know if that was ever discussed. It just happened. Pete understood his role. Sometimes, for the sake of the record, you might have to do something that you don't want to do on your instrument, and I think Pete understood that from the get-go. If you listen to some of the parts he played, especially when it was really kicking, you can imagine horns there instead of steel.

"On 'The Most Beautiful Girl' he did this great slide, it was real high. Well, down in that Quonset hut we had seven EMT plates [EMT 140 plate reverb units], and I dedicated one to Pete and added that on the opposite side of the stereo mix. I think that really benefited the record. I'd generally keep six EMTs in the live room, and I'd use them a lot on the drums, particularly for the rim shots, and also on the vocal. The patchbay that controlled the reverb was to the right of the console, and we would send the signal to the EMT, it would come back, and the return would then go through a tape delay. You'd get a little bump on the end of it and you could use that in different ways — most of the time we'd get the highs out of that little bump, changing the EQ on the tape machine. That would be with the vocal in the centre, even though I'd sometimes use a stereo chamber. Later on I would have a dedicated VSO [Variable Speed Oscillator] so I could control the speed of where that delay was behind the chamber.

"The reverb was part of the Charlie Rich vocal sound, and I think some of it had to do with the way we treated that one delay behind him. It added a nice little warmth."

Bleeding Vocals

"The way we did Charlie Rich sessions changed the way we recorded," explains Lou Bradley. "Hargus 'Pig' Robbins played the piano on most of that stuff, but if Charlie wanted to play then Pig would move over and play electric keyboard, Rhodes or whatever. On 'Behind Closed Doors', Pig was playing the piano, but Charlie still wanted to stand next to it when he was singing, in the middle of the band, and if you listen to the last verse you'll hear a little ghost vocal. That's where they changed the lyric: it was a live vocal except for the last verse.

"Kenny O'Dell was a really good songwriter, but in this case he got some constructive criticism. Billy Sherrill told him, 'That last verse isn't strong enough.' In the original lyric, they kinda went behind closed doors and held hands. Billy said, 'No way they do that. The lyric implies more.'"

And so it was amended: "She's always a lady, just like a lady should be. But when they turn out the lights, she's still a baby to me." Not exactly hardcore stuff. In this case, suggestion was the name of the game.

"That change left me something to deal with," Bradley continues. "The ghost vocal was predominantly coming from the piano mic and I couldn't turn off the piano, so I just had to use some little tricks, putting a little slapback in there for a beat or two. Nobody would ever notice it, I don't recall anyone ever coming to me and saying, 'Boy, I heard a ghost in the last verse.' It's like the time Willie Nelson was driving down the road and passed these two farmers standing out in the field, talking. Somebody said, 'I wonder what they're talking about,' and Willie replied, 'They're discussing the drum sound on the new George Strait record.' I don't think people study records as much as we do.

"After we had success with Charlie Rich standing by the piano, Billy Sherrill wanted to cut everybody that way, and that meant I had to deal with leakage going into the singer's mic. Still, it never hurt the sales of 'Behind Closed Doors'.

"Switching between a vocal with leakage and one that had no leakage made an overdub really obvious, so I learned to turn on the studio speakers when I was mixing and add some leakage to the overdubbed vocal. It was all about feel, and once Billy saw the power of that with Charlie Rich we cut everybody that way. Boy, I tell you, it made the engineer's job tougher, but I knew that was the hand I was going to be dealt so I figured out what I was going to have to do to make it work."

Crack Squad

The routining segment of these Nashville sessions usually only took 10 to 20 minutes, and in an October 1973 interview with Time magazine, Billy Sherrill didn't mince his words explaining how crack musicians who often couldn't read music would learn a tune on the spot from a demo or from the vocalist.

"In New York, you start to change something, you tear up a $700,000 arrangement," he was quoted as saying. "Here we can make the lead sheet of a song in the time it takes to sing it.... All the guys I use are machines. They do exactly what I want 'em to — if the record doesn't hit, I go down in flames."

"The thing with everyone playing so close together was that you'd get a feeling right there, with people just looking each other in the eye," Lou Bradley now says, referring to sessions that would normally entail the recording of anywhere up to a half-dozen takes once tape began to roll. "That's what's missing on a lot of today's records: they're playing to click tracks, whereas those guys played for feel. The dynamic was so much better. The whole recording process is somewhat of a compromise, but if you can capture the live feel then it's really good. In fact, I still get work because of all those years of doing it that way."

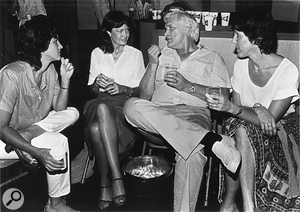

Charlie Rich with Columbia Records staff at the studio's closing party in 1982.Photo: The Mike Curb Family FoundationBack in 1973, the norm was to cut three tracks during a three-hour session. "Occasionally we might do just two," says Bradley, "but what changed things from getting four songs to getting three was multitrack overdubbing. In the case of 'Behind Closed Doors', within an hour we had that record. Then we overdubbed strings, and then they rewrote that last verse, Charlie came in and we overdubbed that.

Charlie Rich with Columbia Records staff at the studio's closing party in 1982.Photo: The Mike Curb Family FoundationBack in 1973, the norm was to cut three tracks during a three-hour session. "Occasionally we might do just two," says Bradley, "but what changed things from getting four songs to getting three was multitrack overdubbing. In the case of 'Behind Closed Doors', within an hour we had that record. Then we overdubbed strings, and then they rewrote that last verse, Charlie came in and we overdubbed that.

"When I first came to Nashville in '69, I'd been used to the musicians wearing earphones when they overdubbed back in Atlanta. Here, some of them would wear earphones, and toward the end most of them did, but some, like Pete Drake, never wore them. He loved that studio, and he'd say, 'When I hear the record it sounds like what I heard sitting here, with all the guys playing around me.' Still, all the overdub sessions for lead vocals, backing vocals and strings were done with a cue system, and that worked pretty well for me. I never was successful doing the out-of-phase deal, but what I found out was, if you work without earphones, you don't have the pitch problems.

"Some singers working with speakers might miss the pitch if they weren't familiar with the melody and didn't know where the next note was, but great singers like Merle Haggard, Tammy [Wynette] and George [Jones] always knew where the next note was going to be. Singing with the speaker, it was like the band was sitting there and playing in front of them, whereas I think a whole lot of psychological stuff goes on with earphones."

Don't Fight It, Feel It

Meanwhile, what with the various musicians' aforementioned abilities, there was also a whole lot of subtle stuff going on with regard to fine-tuning the overall sound.

"When we overdubbed the Shelly Kurland Strings on 'The Most Beautiful Girl', there were eleven players," Bradley recalls, citing seven violins, two violas and two cellos. "I stereo-miked the cellos with KM84s, keeping the mics close to get some presence, and I also single-miked the violas with an 87, placed left or right according to the context of the mix, but the violins were recorded in kind of a classical way, overhead with 87s. Well, for the last part of the song Billy said, 'Shall we mic one of the violins? I want a solo violin there.' Shelly said, 'I'll handle it.' When it got to that part, he just stood up, and if you listen to the record you'll hear that one violin sings out. All he did was stand up and play instead of staying seated in his chair. It was just a natural thing."

And so, according to Bradley, was the mixing process, which took place throughout the recording process.

"You knew you were going for it," he says. "In fact, I had to change my philosophy when I came to Nashville. We'd go into the studio in Atlanta and we might work all night trying to get a feel or a groove. In Nashville, on the other hand, as soon as I started my first session I knew it would be different. I pushed the faders up and, boy, no way was this going to work. After that, what I'd do was look for something out there that I thought was good. It might be a part of whatever the drumer was doing: somebody out there would be doing something I'd like, whether it was the acoustic bass, one of the guitars, or whatever it was, and I'd push that up to where I could hear it and all of a sudden things would start coming together.

"That's what spooks a lot of the newer engineers who've never recorded in that live kind of environment. Until those musicians get it together, what with all the sound charging around the room, it's gonna sound bad. However, once they're locked in, it'll come dancing out of those speakers."